Onze groep bestudeert de wederzijdse communicatie tussen epithelium en stroma. Deze orkestreren de ontwikkeling van epitheliale structuren in de pancreas en schildklier. Tevens bestuderen we de endocytose in de schildklier en nieren in gezonde en pathologische weefsels.

Ons lichaam bestaat uit vele verschillende soorten cellen waaronder epitheelcellen. Deze vervullen verschillende functies: passieve bescherming via de huid, actieve verdediging dankzij de lymfocyten, absorptie van voedingsstoffen door de darmcellen, gasuitwisseling in de longen, secretie van enzymen door de pancreas, productie van hormonen door de schildklier, … In het begin was er nochtans slechts één cel, afkomstig van de ontmoeting van een zaadcel en een eicel. Deze cel, die totipotent wordt genoemd, ondergaat gedurende de embryonale ontwikkeling een groot aantal splitsingen wat aanleiding geeft tot de voorlopercellen van de verschillende celsoorten waaruit het volwassen lichaam bestaat. Terwijl elk type voorlopercel zich vermenigvuldigt door successieve delingen, beginnen ze zich ook te organiseren om een bepaalde structuur te vormen (bijvoorbeeld: de luchtpijptakken) en geleidelijk aan specialiseren ze zich om een specifieke functie te vervullen (bijvoorbeeld: het uitwisselen van koolstofdioxide voor zuurstof).

De groep van Prof. C. Pierreux bestudeert de overgang van epitheelcellen in een proliferatieve staat naar een gespecialiseerde en georganiseerde staat, in de embryonale ontwikkeling van pancreas en schildklier. Deze twee organen ontstaan als een uitstulping van de primitieve darm maar hebben zich anders georganiseerd. Het eerste in een netwerk van vertakte kanalen die gespecialiseerd zijn in het afscheiden en het transporteren van enzymen naar de twaalfvingerige darm (voor de spijsvertering). Het tweede orgaan bestaat uit een aantal gesloten zakjes die voor de interne productie van hormonen zorgen (naar het bloed). Het laboratorium heeft aangetoond dat de epitheelcellen van beide organen eerst een ongestructureerde driedimensionale cluster vormen door een groot aantal celsplitsingen. Hierna herorganiseren ze zich in gespecialiseerde en gepolariseerd monolagen (figuur). Gedurende de eerste fasen van kanker, waarin de cellen kwaadaardige veranderingen ondergaan, is de overgang van cluster naar monolaag omgekeerd, alsof de film van het leven werd omgedraaid. Dit concept van “omgekeerd oncogenesis ontogenesis” (het ontstaan van kanker reproduceert de ontstaansgeschiedenis van het individu, maar in tegengestelde richting) is de rode draad van het onderzoek van Prof. C. Pierreux.

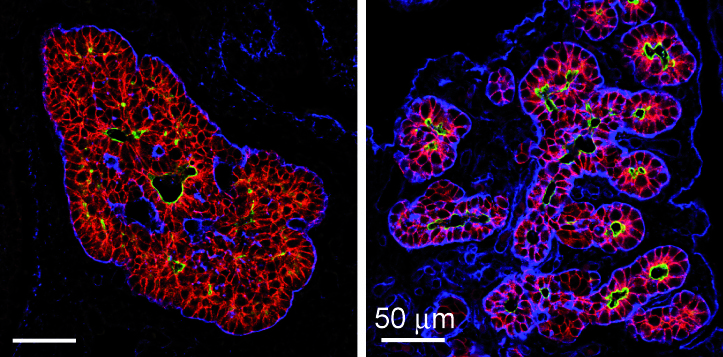

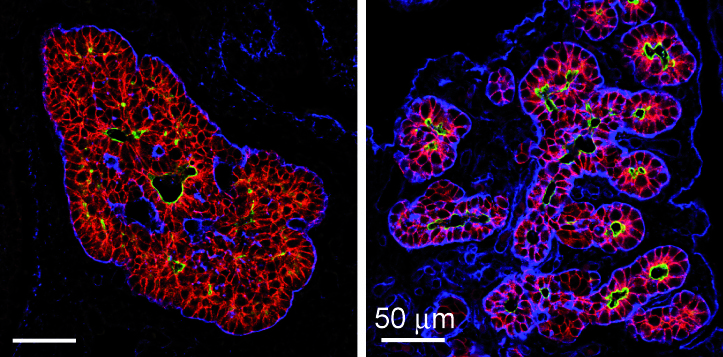

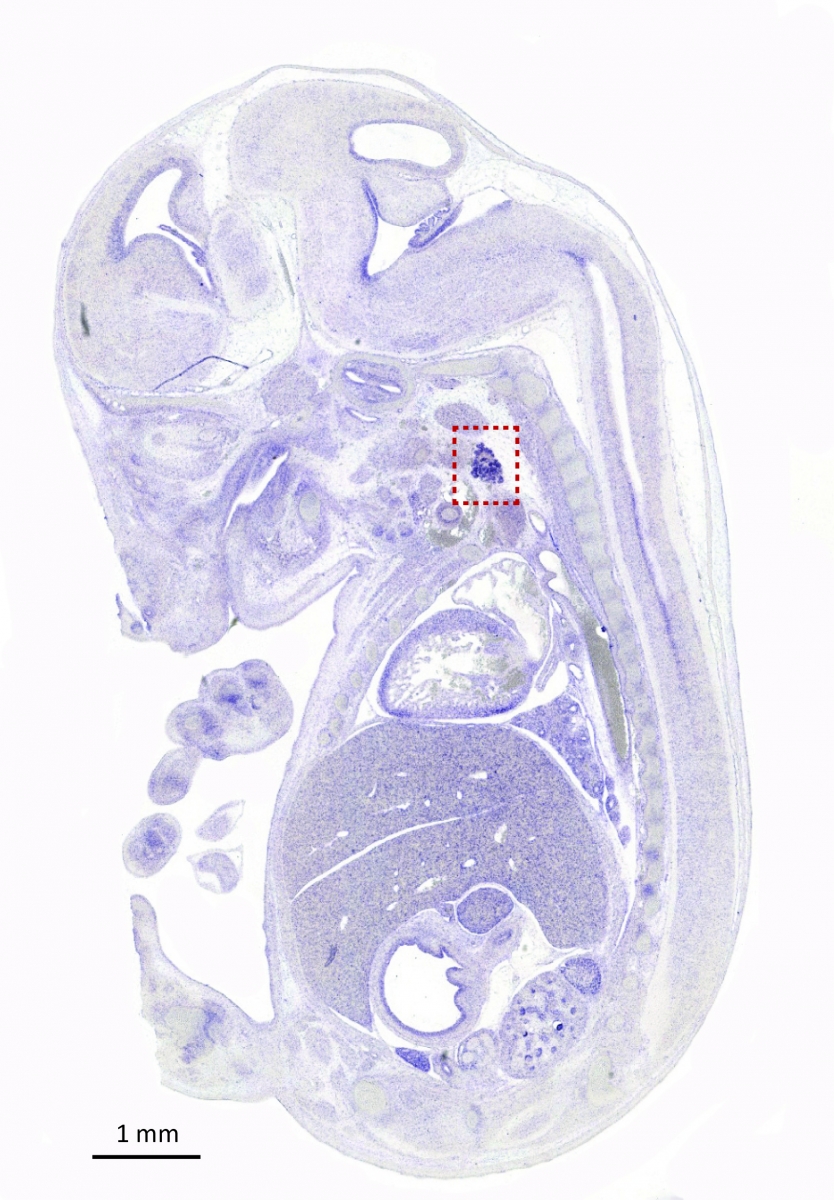

Legend:

Herschikking van de cellen van de pancreatische knop tot een epithelium. In het begin van de embryonale ontwikkeling van de pancreas vormen de epitheelcellen een meercellige massa. Hierna reorganiseren ze zich in gepolariseerde monolagen met een duidelijk apicaal domein, die de vaatholte van de pancreatische kanalen aftekent. De epitheelcellen worden van hun omgeving gescheiden door een basale membraan (in het blauw). (van Hick et al. 2009).

Celsplitsing of cel specialisatie?

De epitheelcellen van de volwassen pancreas en van de volwassen schildklier ondergaan geen celsplitsingen meer. Zij behouden hun gespecialiseerde functie tenzij het omgekeerd proces wordt ontketend. Deze transformatie leidt dan tot kanker. De factors verantwoordelijk voor deze verandering zijn nog slecht gekend omdat het moeilijk is deze te identificeren wanneer de kanker al gevestigd is. Om dit fundamenteel probleem van oncogenesis te omzeilen, heeft Christophe Pierreux ervoor gekozen om de beslissende stappen van ontogenesis te bestuderen. Zijn expertise, samen met de celbiologische benaderingen van Prof. P. Courtoy uit de eenheid CELL van het De Duve Instituut, hebben ertoe geleid een belangrijke factor te identificeren die zowel genen van de celdivisie kan aanzetten en genen van de celspecialisatie kan uitschakelen.

Het belang van de omgeving

De juiste ontwikkeling en de goede werking van organen (lever, nieren, pancreas, borstklieren of schildklier) hangt af van de wederzijdse communicatie die bestaat tussen drie belangrijk cel types. De epitheelcellen, georganiseerd in monolagen, vervullen functies die specifiek zijn aan het orgaan. Ze worden gevoed door de bloedvaten (endotheelcellen) die hen ook signalen verzenden. Het interstitieel weefsel (mesenchymale cellen) ondersteunt de epitheelcellen en geeft tegelijkertijd instructies. Deze signalen tussen het epithelium en zijn omgeving (endotheelcellen van de bloedvaten en de mesenchymale cellen van het interstitieel weefsel) worden uitgewisseld, worden overgebracht naar de celkern van de epitheelcellen via proteïnen die de genexpressie controleren en zo het lot van de cel herprogrammeren tot celsplitsing, celmigratie, celspecialisatie, vormverandering of zelfmoord. De uitgewisselde signalen zijn cruciaal voor de vorming en de homeostase van de epitheliale organen, maar zij kunnen ook omgeleid of misbruikt worden gedurende de ontwikkeling van een tumor.

Communiceren in het privé

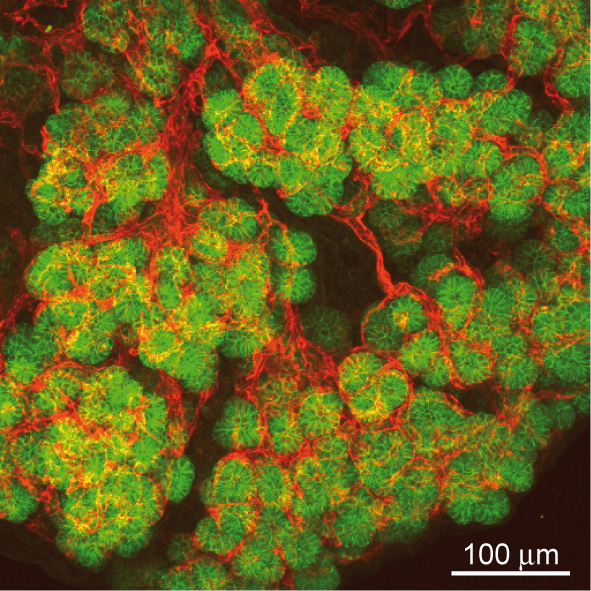

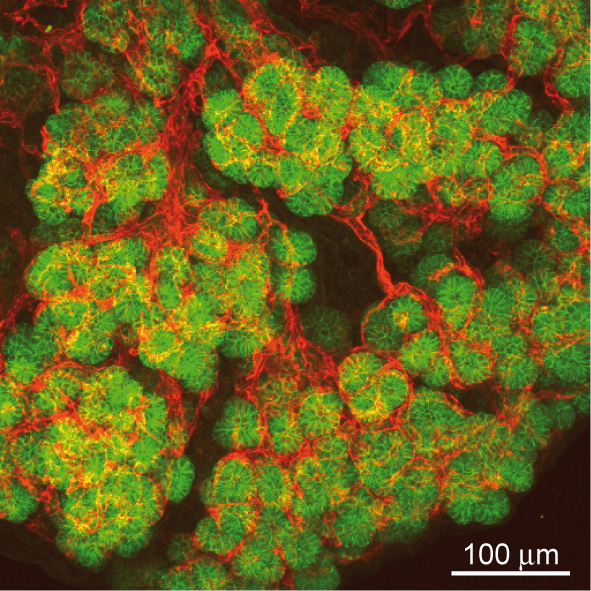

Wanneer een tumor een kritisch massa bereikt, zendt hij signalen uit om bloedvaten aan te trekken. Deze vaten leiden niet alleen het bloed van gezonde weefsels af (om de groei van de tumor te steunen), maar ze geven ook aanleiding tot de verspreiding van tumorcellen in het lichaam van de patiënt en hun vestiging op zekere afstand van de primaire tumor. Deze metastasen kunnen dodelijk zijn. Nog steeds volgens het concept dat “oncogenesis ontogenesis omkeert” richt de groep van Prof. C. Pierreux zijn onderzoek ook op de interacties die bestaan tussen de epitheelcellen (figuur; hiertegen in het groen) en de bloedvaten (in het rood) tijdens de embryonale vorming van de pancreas en de schildklier. Hun analyse wijst erop dat er nauwe interacties en ononderbroken signalen aanwezig zijn, zowel in de pancreas als in de schildklier. Het onderstaan van deze taal en de intracellulaire gevolgen zijn belangrijk zowel voor de embryologie als voor de geneeskunde. Dit zou kunnen leiden tot het identificeren van biomarkers of het ontwikkelen van therapeutische hulpmiddelen.

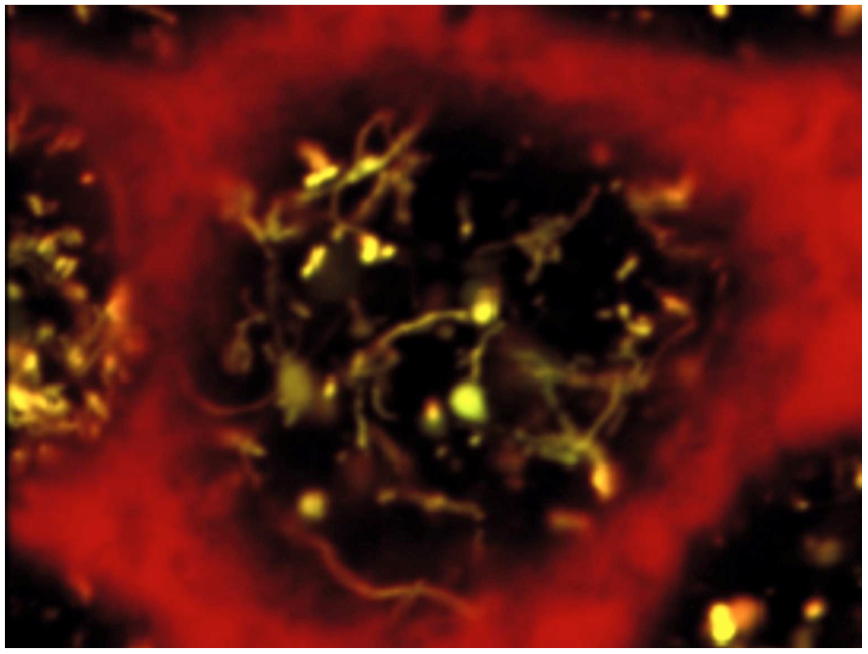

Legend :

Innig contact tussen het epithelium en de endotheelcellen van de bloedvaten in de pancreas. Projectie van 40 confocale beelden die op een 40 micrometer-dik pancreatisch weefsel werden verkregen. De endotheelcellen (in het rood) tonen en nauwe verbinding met de epitheelcellen van de embryonale pancreas (in het groen).

Epithelial parenchyma form during embryogenesis as polarized monolayers and acquire their characteristic differentiation by interplay of intrinsic transcriptional regulation and key extrinsic signals from the instructing stroma. At the subcellular level, stabilization of polarity is also linked to endocytic trafficking. In the adult, apical endocytosis and lysosomal processing are essential for kidney and thyroid function. Research aims at (1) delineating the signals and effects of epithelial:stromal reciprocal interactions in the control of epithelial organogenesis in mouse embryos, and (2) better understanding the role of apical endocytosis in epithelial homeostasis and disease.

Epithelial organogenesis and differentiation

We focus on epithelial-endothelial communications during the development of two endoderm-derived organs, the pancreas and the thyroid. For these two organs, we developed unique 3D culture systems and we routinely exploit leading-edge microscopy on explant cultures as well as on genetically engineered tissues (movie). By combining these in vivo and ex vivo models and tools, we want to address the following questions: which signals drive epithelial morphogenesis towards a branched network of open ducts (exocrine pancreas) or towards independent closed follicles (thyroid)? How does the epithelium recruit blood vessels and how do the recruited endothelial cells instruct the epithelial cells?

Movie: Close association of epithelial cells with endothelial in the developing thyroid. In-depth topological relations between thyrocyte progenitors (nuclei in green) and endothelial cells (in red) in ex vivo cultured thyroid, analysed by multiphotons microscopy. The movie shows a succession of 60 confocal images taken every micrometer.

We have shown that during pancreatic organogenesis, progenitors first form a proliferating 3D mass of non-polarized epithelial cells that then reorganize into a specialized monolayer. This epithelial transition from a mass to a monolayer requires a coordinate and dynamic interaction with their environment, composed of mesenchymal and endothelial cells. We identified SDF-1 (Stromal cell-Derived Factor-1) as an important signal, produced by the mesenchymal cells, for the reorganization of the pancreatic and salivary epithelial masses into monolayers (Hick et al., 2009). (Figure)

Figure: Branching morphogenesis in the pancreas. Reorganization in the early pancreatic bud of the multicellular mass of epithelial cells labelled for E-cadherin (left, red) into polarized monolayers with distinct apical domains (mucin, green) and their merging to create tubules (right). Laminin (blue) delineates basement membranes (From Hick et al., 2009).

Three-dimensional analysis of the developing pancreas by multiphoton microscopy uncovered a dense and close association of the epithelium with endothelial cells (Figure vessels). Our in vivo and in vitro data show that endothelial cell recruitment depends on VEGF production by the pancreatic epithelium. Interestingly, localized VEGF expression in the epithelial trunk cells is critical to recruit endothelial cells around the trunk, at a distance from the tip cells. We further show that endothelial cells, in turn, focally restrict acinar differentiation (Pierreux et al., 2010).

Figure: Epithelial - endothelial interactions in the pancreas. Projections of 40 confocal images showing the dense and close association of pancreatic epithelial cells, labelled for E-cadherin (green), with endothelial cells, labelled for PECAM (red), in the embryonic pancreas.

These data demonstrate that paracrine epithelial:mesenchyme and epithelial:endothelial communications are crucial for pancreas development. Our studies on pancreatic epithelial morphogenesis and on the role of endothelial cells were followed and confirmed by others (Villasenor, 2010; Sand, 2011; Magenheim, 2011).

Recently, we also investigated the role of endothelial cells during thyroid development. In contrast to the pancreas, all thyroid progenitors express VEGF and its level of expression is the highest in e14.5 embryos (Figure Vegfa-ISH). Thyroid-specific Vegfa inactivation reveals that VEGF is required for endothelial cell recruitment at the time of epithelial folliculogenesis. In the absence of blood vessels, thyrocytes progenitors do not organize in large follicles: small lumens are visible but these are shared by few cells or are found intracellularly (Figure ME). Using an ex vivo thyroid culture system, we confirmed the follicular defect and demonstrated that culture medium conditioned by endothelial progenitor cells can rescue and stimulate follicle formation (Hick et al., 2013).

Figure: Vegfa is highly expressed in the thyroid. In situ hybridization with a Vegfa antisense probe show strong staining of the thyroid bud in e14.5 embryo (sagittal section). Thyroid region is boxed (From Hick et al., 2013).

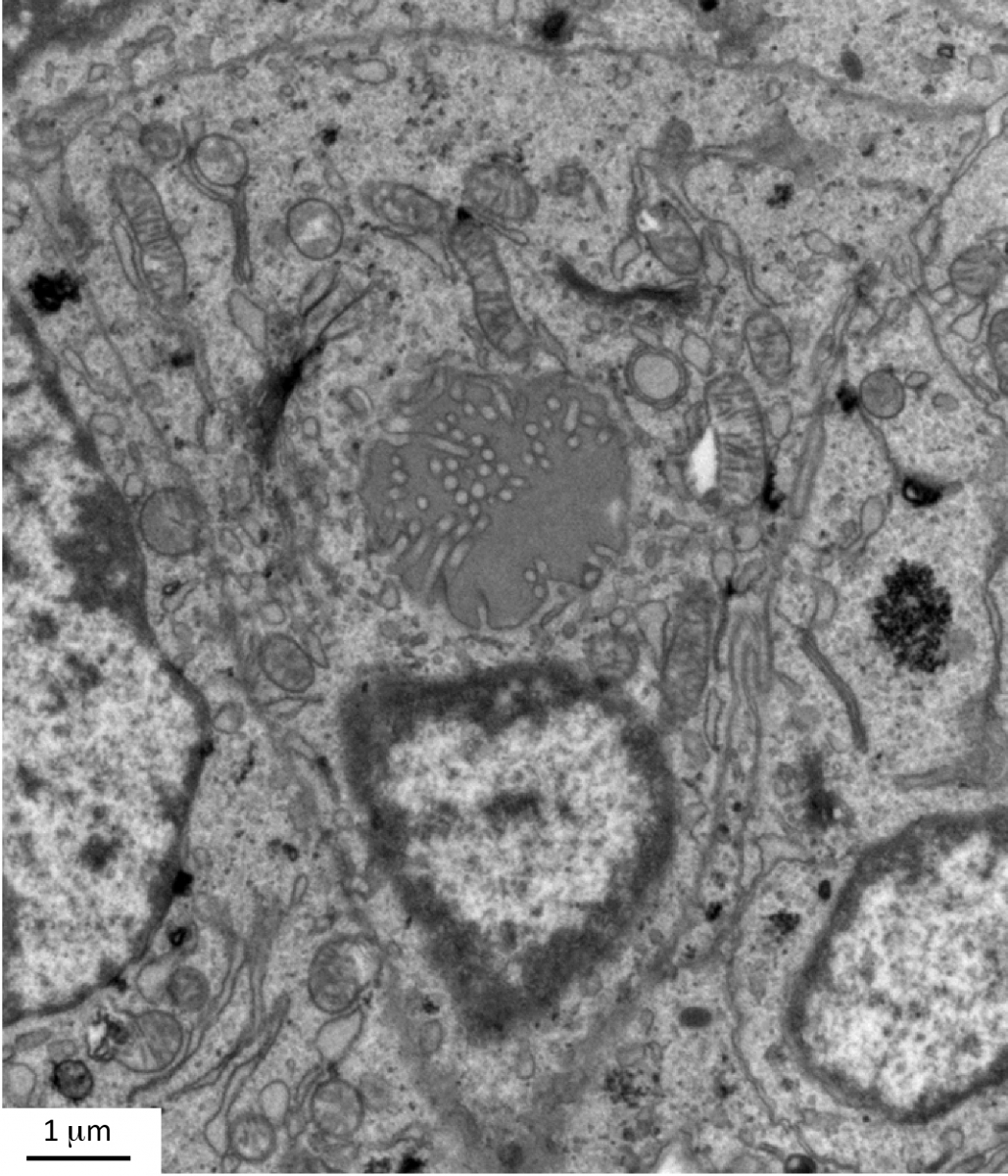

Figure: Defective lumen formation in Vegfa conditional knockout. Electron microscopy of Vegfa conditional knockout thyroid showing a thyrocyte progenitor containing an intracellular lumen with membranous projections (From Hick et al., 2013).

Current work focuses on the network of reciprocal juxtacrine communications between epithelial cells and blood vessels, on their intracellular decoding by epithelial transcription factors during mouse development, and on their implications during human carcinogenesis.

Epithelial homeostasis and apical endocytosis diseases

We focus on two organs with most active apical endocytosis, the kidneys and the thyroid. Due to extraordinary efficiency of apical receptor-mediated endocytosis, kidney proximal tubular cells (PTCs) are a unique system to study machineries of apical endocytic trafficking and their involvement in kidney diseases. Using KO mice for the chloride channel, ClC-5, as model of Dent’s disease (familial predisposition to kidney stones), we found that this channel is essential for apical endocytic recycling (Christensen et al, 2003). Using similar systems, we demonstrated that circulating lysosomal enzymes are continuously filtered in glomeruli, reabsorbed by megalin-mediated endocytosis, and transferred into lysosomes to exert their function, thus providing a major source of enzymes to PTCs. These observations extend the significance of megalin in PTCs and have several physiopathological and clinical implications (Nielsen et al, 2005).

Recently, we identified a key role of class III PI3-kinase/VPS34 in apical recycling of endocytic receptors. In vitro, VPS34 inhibition with LY294002 induced selective apical endosome swelling and sequestration of the endocytic receptor, megalin. This effect was reversible: removal of the inhibitor induced a spectacular burst of recycling tubules and restored the megalin surface pool (Fig. 3). In mouse pups PTCs, conditional Vps34 inactivation also led to vacuolation and intracellular megalin redistribution. We anticipate that these KO mice and reversible PI3K inhibition will help further identify rate-limiting actors of apical endocytosis, of both fundamental and clinical importance (Carpentier et al, 2013).

Figure: Reversible PI3K inhibition as a tool to synchronize apical endocytic recycling. Apical endosomes of polarized PTCs were loaded by endocytosis of fluorescent tracers, then PI3K was inhibited by LY294002 to induce endosome vacuolation. PI3K restoration by LY294002 chase reverses vacuolation and triggers a spectacular burst of recycling tubules (From Carpentier et al, 2013).

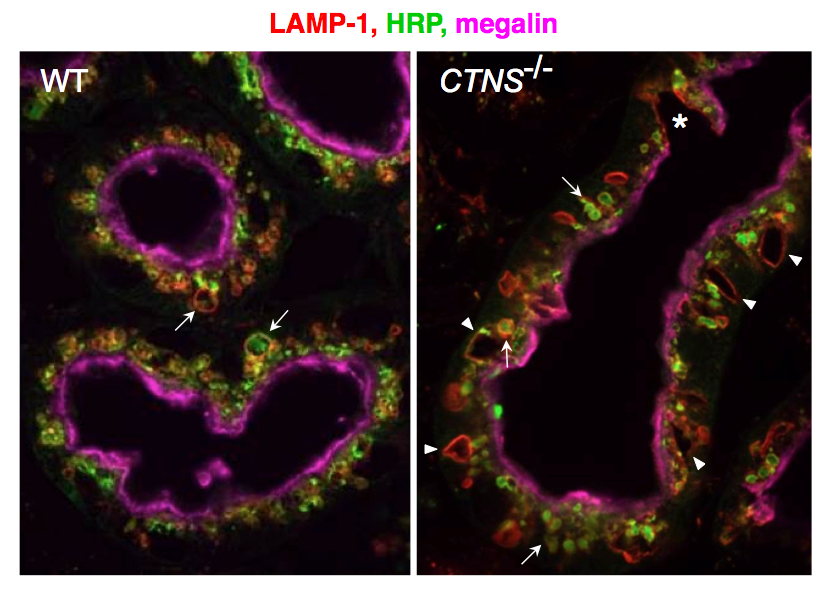

Current investigations are also addressing the pathophysiology of cystinosis, a multisystemic lysosomal disease due to defective lysosomal membrane cystine/H+ antiporter, cystinosin. This disease first manifests itself in kidney as a generalized PTC dysfunction, referred to as kidney Fanconi syndrome. Endocytosis of ultrafiltrated plasma proteins rich in disulfide bridge rich must be the main source of lysosomal cystine in PTCs. Current analysis of cystinosin KO mice helps us understanding how cystine accumulation causes apical PTC lysosomal overload linked to dedifferentiation, prior to huge cystine crystals and eventual atrophy (Fig. 4). We identified three adaptation mechanisms: vesicular efflux of soluble cystine, lysosomal cysteine crystal discharge, and apoptotic shedding with proliferative epithelial repair (Gaide-Chevronnay et al, 2014). In cystinotic thyroid, defective lysosomal generation of thyroid hormones from thyroglobulin induces a strong TSH response causing thyrocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia. In collaboration with S. Cherqui (UCSD, CA), we demonstrated that cystinotic thyroid lesions could be fully prevented by grafting hematopoietic stem cells and currently decipher the correction of epithelial defects in kidneys and thyroid across their basal lamina.

Figure: Progression of PTC lesions in cystinosin KO mice. At 6 months (a), only PTCs immediately following glomeruli (overlaid in pale green) show extensive apical vacuolation (arrows), indicating osmotic swelling of lysosomes by accumulating cystine, contrasting with integrity of kidney elsewhere, including more distal PTCs. (b) At 12 months, proximal PTCS are now completely atrophic (arrowheads) and more distal PTCs harbour numerous crystals (appearing as empty spaces with characteristic geometric shape; red triangles).

Steed E, Elbediwy A, Vacca B, Dupasquier S, Hemkemeyer SA, Suddason T, Costa AC, Beaudry JB, Zihni C, Gallagher E, Pierreux CE, Balda MS, Matter K.

J Cell Biol. 2014; 204(5):821-38.

Hick AC, Delmarcelle AS, Bouquet M, Klotz S, Copetti T, Forez C, Van Der Smissen P, Sonveaux P, Collet JF, Feron O, Courtoy PJ, Pierreux CE.

Dev Biol. 2013; 381(1):227-40.

Carpentier S, N'Kuli F, Grieco G, Van Der Smissen P, Janssens V, Emonard H, Bilanges B, Vanhaesebroeck B, Gaide Chevronnay HP, Pierreux CE, Tyteca D, Courtoy PJ.

Traffic. 2013; 14(8):933-48.

Pierreux CE, Cordi S, Hick AC, Achouri Y, Ruiz de Almodovar C, Prévot PP, Courtoy PJ, Carmeliet P, Lemaigre FP.

Dev Biol. 2010; 347(1):216-27.

Lima WR, Parreira KS, Devuyst O, Caplanusi A, N'kuli F, Marien B, Van Der Smissen P, Alves PM, Verroust P, Christensen EI, Terzi F, Matter K, Balda MS, Pierreux CE, Courtoy PJ.

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010; 21(3):478-88.

Hick AC, van Eyll JM, Cordi S, Forez C, Passante L, Kohara H, Nagasawa T, Vanderhaeghen P, Courtoy PJ, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP, Pierreux CE.

BMC Dev Biol. 2009; 9:66.

Pierreux CE, Poll AV, Kemp CR, Clotman F, Maestro MA, Cordi S, Ferrer J, Leyns L, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP.

Gastroenterology. 2006; 130(2):532-41.

Poll AV, Pierreux CE, Lokmane L, Haumaitre C, Achouri Y, Jacquemin P, Rousseau GG, Cereghini S, Lemaigre FP.

Diabetes. 2006; 55(1):61-9.

Clotman F, Jacquemin P, Plumb-Rudewiez N, Pierreux CE, Van der Smissen P, Dietz HC, Courtoy PJ, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP.

Genes Dev. 2005; 19(16):1849-54.

Pierreux CE, Vanhorenbeeck V, Jacquemin P, Lemaigre FP, Rousseau GG.

J Biol Chem. 2004; 279(49):51298-304.

van Eyll JM, Pierreux CE, Lemaigre FP, Rousseau GG.

J Cell Sci. 2004; 117(Pt 10):2077-86.

Pierreux CE, Nicolás FJ, Hill CS.

Mol Cell Biol. 2000; 20(23):9041-54.

Lehmann K, Janda E, Pierreux CE, Rytömaa M, Schulze A, McMahon M, Hill CS, Beug H, Downward J.

Genes Dev. 2000; 14(20):2610-22.

DIFFERENTIATIE, ENDOCYTOSE EN EPITHELIALE HOMEOSTASE