Nous essayons de comprendre pourquoi les lymphocytes T infiltrant les tumeurs sont incapables de tuer les cellules tumorales, et de trouver des stratégies applicables en clinique pour surmonter ce blocage. Nous avons découvert que le dysfonctionnement des lymphocytes infiltrant les tumeurs humaines peut être dû à la présence de galectine-3, une lectine abondante dans les tumeurs.

Des lymphocytes T tueurs de cellules cancéreuses

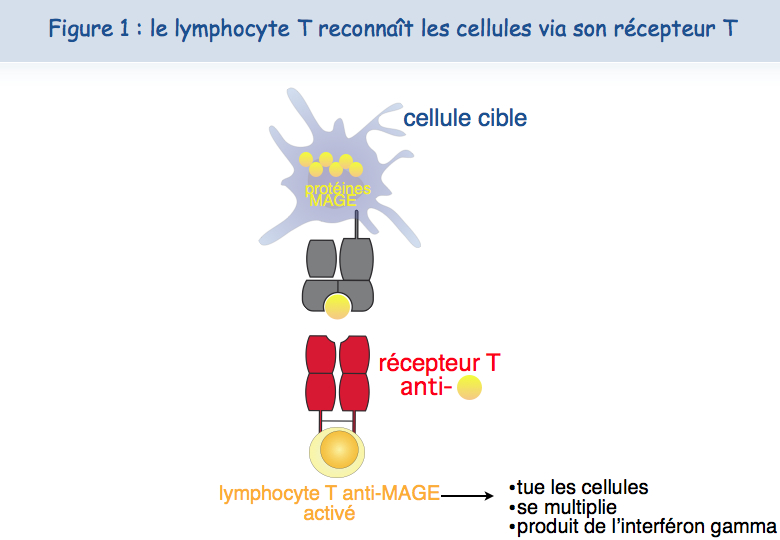

Que notre système immunitaire puisse nous débarrasser de certains cancers est un rêve dont les bases expérimentales datent des années 40. Des souris opérées d’une tumeur étaient capables d’éliminer des cellules de cette même tumeur lorsqu'elles leur étaient injectées mais n'étaient pas capables d'éliminer des cellules d'une autre tumeur. Cela signait l’intervention du système immunitaire. Celui-ci fonctionne avec des cellules spécialisées parmi lesquelles certains globules blancs, appelés lymphocytes T, portent des récepteurs susceptibles de reconnaître des structures moléculaires étrangères à notre propre organisme, appelées antigènes. Nous disposons de plusieurs dizaines de millions de lymphocytes T différents, chacun porteur d’un seul type de récepteur susceptible de reconnaître un antigène particulier. Cette reconnaissance de l'antigène par le lymphocyte T va entraîner la multiplication et l’activation du lymphocyte. Certains deviennent des lymphocytes cytolytiques, capables d'une part de faire éclater la cellule sur laquelle ils reconnaissent leur antigène et d'autre part de produire des molécules qui servent de messages pour d'autres cellules. Un de ces messages est l'interféron-gamma.

La découverte d'antigènes de tumeurs

Les lymphocytes T peuvent nous guérir d’infections virales car les cellules infectées par des virus portent des antigènes viraux. Personne ne savait, jusqu’il y a une vingtaine d’années, s'il existait des antigènes spécifiques sur les tumeurs humaines et donc si les lymphocytes T humains pouvaient distinguer les cellules tumorales des cellules normales. Il ne fait plus de doute aujourd’hui que la majorité des cancers humains présentent des antigènes spécifiques des cellules cancéreuses. L’Institut de Duve a joué un rôle déterminant pour démontrer ce concept, car les premiers antigènes tumoraux y ont été découverts par l'équipe de Thierry Boon. Pierre van der Bruggen et Catia Traversari étaient en première ligne. Plusieurs dizaines de ces antigènes reconnus par des lymphocytes T cytolytiques sont maintenant connus, et beaucoup restent à découvrir. Mais certains d’entre eux présentent d’ores et déjà des caractéristiques qui en font d’excellents candidats pour le développement d’une thérapie basée sur l'activation des lymphocytes T anti-tumeur. La présence d'antigènes tumoraux résulte de l’expression de gènes, tels que MAGE, qui sont exprimés dans beaucoup de tumeurs mais pas dans les tissus normaux (Figure 1).

Outre cette spécificité tumorale, une deuxième caractéristique des antigènes MAGE est leur présence sur beaucoup de cancers différents, permettant d’utiliser chez beaucoup de malades le même vaccin thérapeutique. On parle ici de vaccin thérapeutique par opposition aux vaccins prophylactiques.

Vaccination thérapeutique anti-tumeur

Les premières vaccinations thérapeutiques avec des antigènes MAGE débutèrent en 1994 chez des patients atteints de mélanome. Parmi les patients vaccinés, 15 % ont montré une régression significative de leur cancer alors que la fréquence de régression spontanée dans le mélanome métastatique est estimée à moins de 0,5 %. Ces régressions, parfois complètes et durables, ont été obtenues en l'absence de tout effet secondaire, ce qui nous paraît être un avantage déterminant par rapport aux traitements anticancéreux classiques tels que la chimiothérapie.

L’essentiel pour l'avenir sera de comprendre pourquoi les vaccinations thérapeutiques échouent dans la majorité des cas. Avons-nous été incapables de déclencher une réponse des lymphocytes chez ces malades ? Leur tumeur est-elle résistante à l’attaque immunitaire ? Et dans chaque cas, pourquoi ?

Au début de notre programme clinique, nous pensions que le système immunitaire d’un malade cancéreux restait “endormi” face aux antigènes exprimés par la tumeur mais qu'un vaccin contenant les bons ingrédients pourrait induire de fortes réponses de lymphocytes T qui détruiraient les cellules cancéreuses.

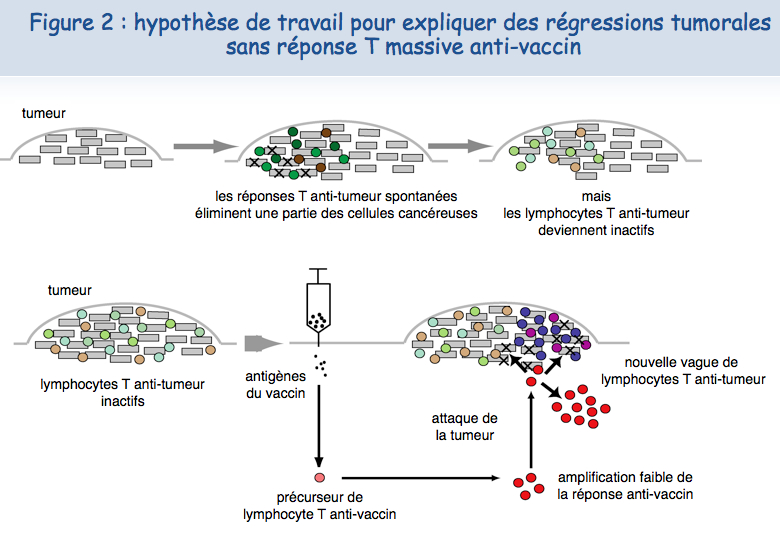

Différentes observations faites par l'équipe de Pierre Coulie à l'Institut de Duve et par celle de Thierry Boon ont conduit à proposer un autre scénario pour expliquer les régressions tumorales induites par vaccination. Les patients atteints de mélanome métastatique développent des réponses immunitaires spontanées contre certains antigènes tumoraux exprimés par leur tumeur. Ces lymphocytes anti-tumoraux se concentrent dans les métastases, mais deviennent incapables d’agir efficacement contre les cellules tumorales, vraisemblablement à cause de mécanismes de résistance mis en place par la tumeur. Chez certains malades, un petit nombre de lymphocytes T induits par le vaccin migreraient dans la tumeur et parviendraient, par un mécanisme inconnu, à activer ou réactiver d’autres lymphocytes anti-tumoraux, permettant à ces derniers de proliférer et de détruire les cellules cancéreuses (Figure 2).

Un nouveau mécanisme d'épuisement des lymphocytes

Analyse sur des lymphocytes cultivés au laboratoire

Plusieurs études indiquent que les lymphocytes infiltrant les tumeurs ne fonctionnent pas correctement. On parle alors de dysfonctionnement des lymphocytes T.

Des chercheurs de l’équipe de Pierre van der Bruggen ont mis en évidence un nouveau mécanisme de dysfonctionnement des lymphocytes T humains et ont découvert des approches pour corrige ce dysfonctionnement. Ils ont initialement observé que la plupart des lymphocytes T cytolytiques, suite à un contact avec des cellules présentant l'antigène, perdent pendant plusieurs jours leur capacité à tuer des cellules présentant l'antigène et à sécréter de l'interféron-gamma.

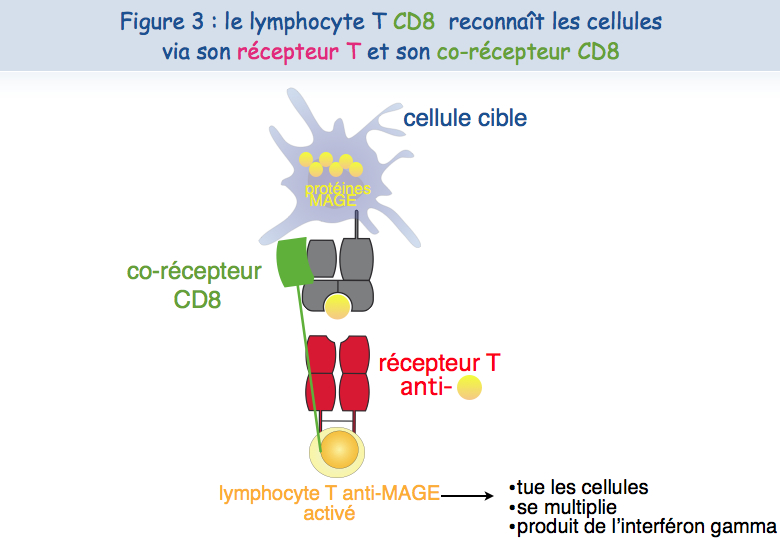

Différentes approches expérimentales ont été mises en œuvre pour essayer de comprendre ce dysfonctionnement. Un lymphocyte T cytolytique a besoin au minimum de deux récepteurs pour reconnaître l'antigène et pour être activé : le TCR et le CD8 (Figure 3).

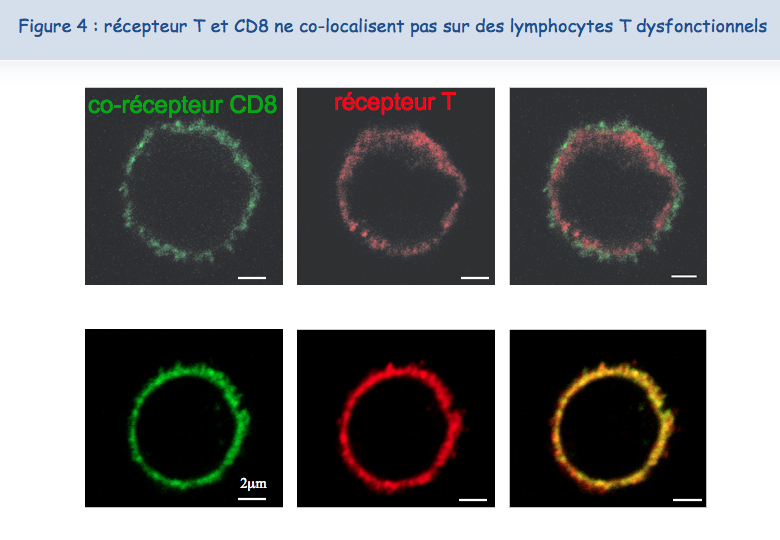

Le nouveau microscope récemment acquis par l'Institut de Duve et les compétences de Pierre Courtoy et Patrick Van Der Smissen de l'unité de Biologie Cellulaire ont permis d'établir que les deux récepteurs sont proches l'un de l'autre (co-localisés) à la surface des lymphocytes fonctionnels, tandis que ces deux récepteurs ne sont pas co-localisés à la surface des lymphocytes dysfonctionnels (Figure 4).

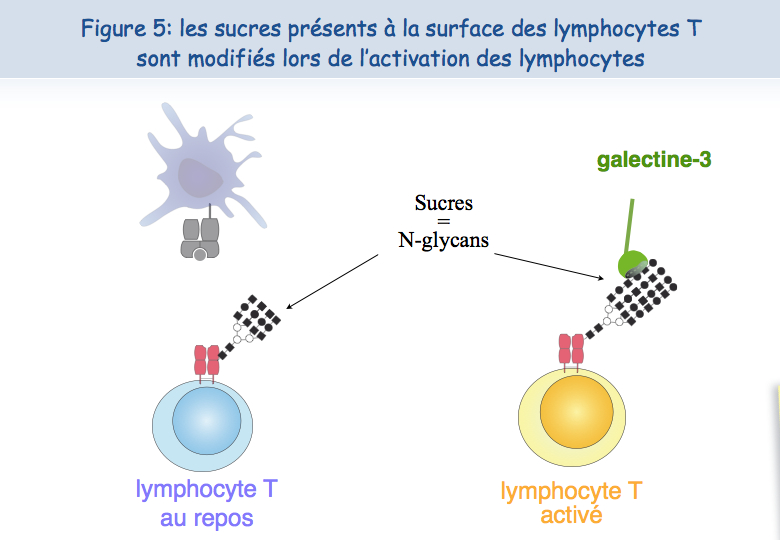

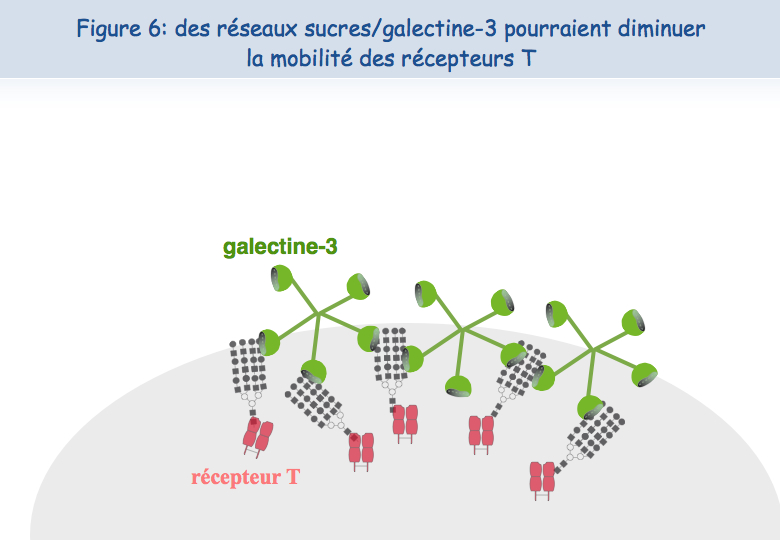

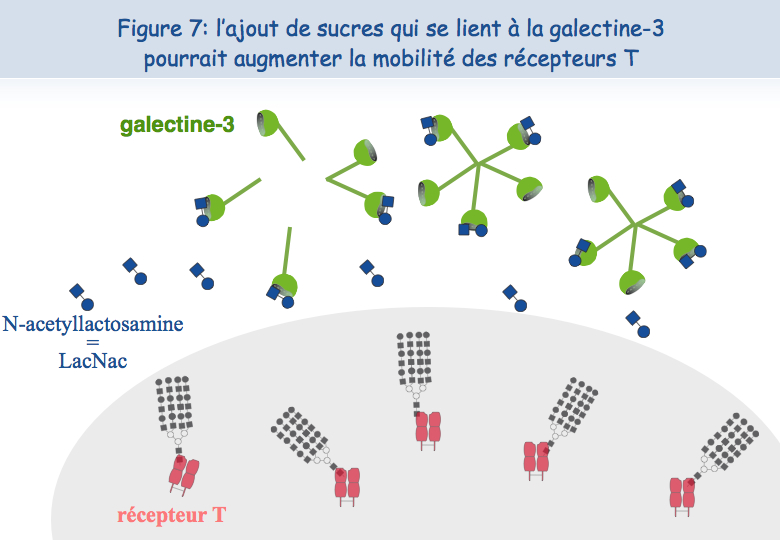

Pour expliquer cette absence de co-localisation, les chercheurs ont envisagé la possibilité que ces récepteurs soient retenus à des endroits différents de la membrane. En ce qui concerne le TCR, il semblerait que lorsque les lymphocytes sont mis en présence de l'antigène trop fréquemment, le TCR se charge en "sucres". Une molécule, appelée galectine-3, se lie alors à ces sucres et lie ainsi les TCR. Les TCR perdent leur mobilité et ne peuvent plus interagir avec l'autre récepteur, le CD8 (Figures 5, 6 & 7).

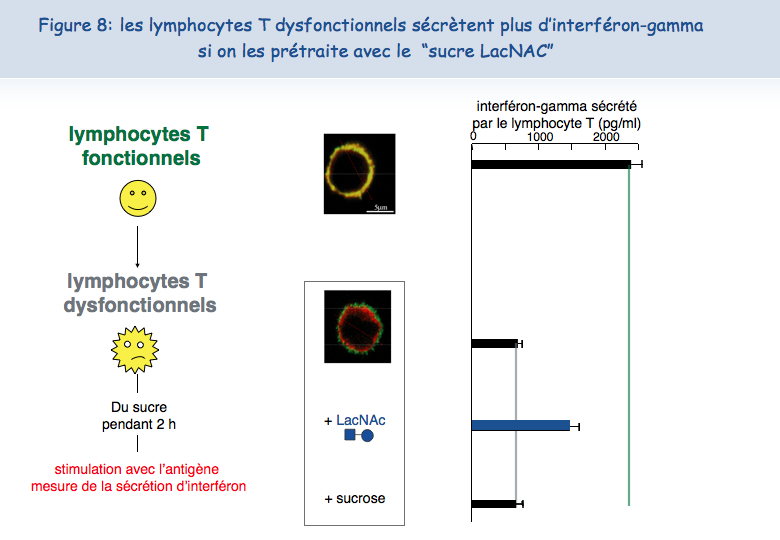

Pour tester cette hypothèse d'une absence de mobilité du TCR à la surface des lymphocytes T dysfonctionnels, ceux-ci ont été mis en présence d'un sucre qui se lie à la galectine-3, le LacNAc. Deux heures de traitement avec du LacNAc ont permis de récupérer une grande partie de la co-localisation du TCR et du CD8. Les lymphocytes T traités au LacNAc avaient également récupéré leur capacité à sécréter de l'interféron-g suite à une stimulation avec l'antigène (Figure 8).

Analyse des lymphocytes infiltrant des tumeurs de patients

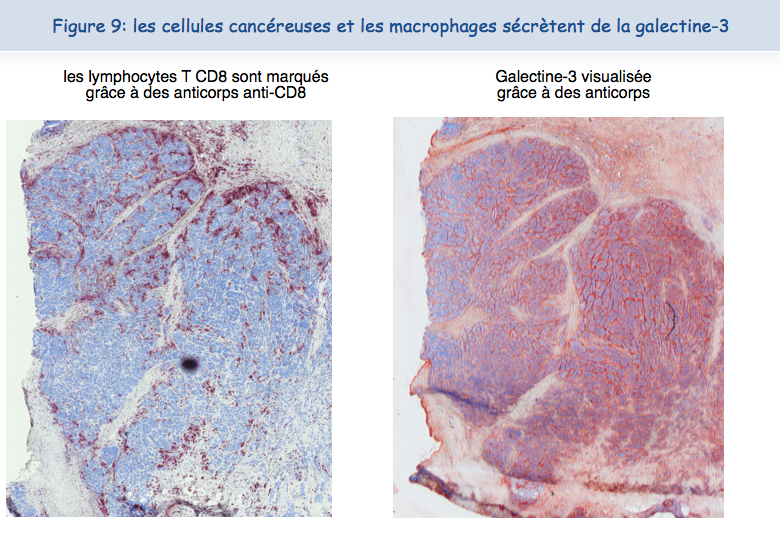

On trouve très fréquemment de grandes quantités de galectine-3 dans les tumeurs (Figure 9).

Il était tentant de penser que, comme pour les lymphocytes T cultivés au laboratoire, les lymphocytes T qui se trouvent dans les tumeurs étaient dysfonctionnels en raison de cette présence de galectine-3. Grâce à la collaboration des médecins des cliniques Saint-Luc à Bruxelles, nous avons pu isoler des lymphocytes T humains à partir de tumeurs. A la surface de ces lymphocytes T, les TCR et les CD8 n'étaient pas co-localisés. Ces lymphocytes étaient incapables de sécréter de l'interféron-gamma suite à une stimulation par des cellules tumorales. Ces résultats indiquaient clairement que le dysfonctionnement des lymphocytes infiltrant les tumeurs était corrélé à une absence de co-localisation du TCR et du CD8.

Réveiller des lymphocytes T épuisés

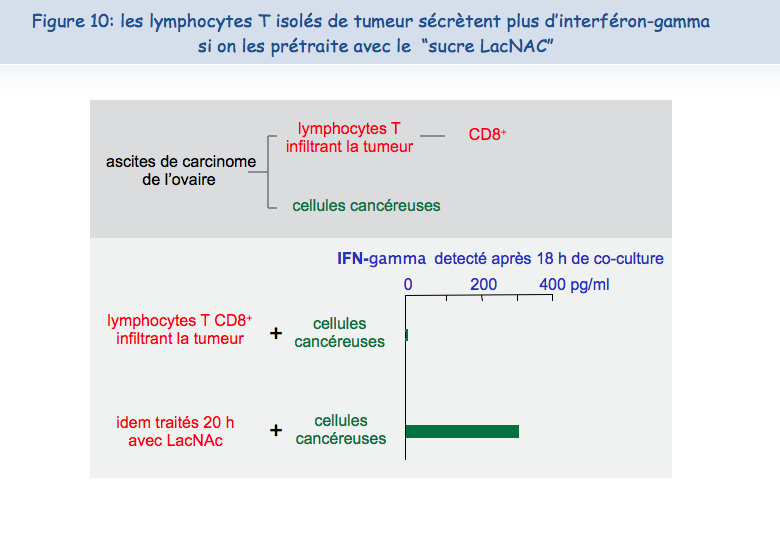

L'observation suivante fut la plus importante : il était possible de réveiller les fonctions des lymphocytes T infiltrant les tumeurs. Après une nuit d'incubation en présence de LacNAc (le sucre qui se lie à la galectine-3), les lymphocytes avaient récupéré la co-localisation du TCR et du CD8 et la capacité à sécréter de l'interféron-gamma (Figure 10).

Ces résultats obtenus ex vivo nous permettent de suggérer qu'injecter dans les tumeurs du LacNAc, ou d'autres antagonistes de la galectine, pourrait restaurer au moins temporairement les fonctions des lymphocytes T et créer ainsi des conditions favorables à une réponse anti-tumorale efficace. Combiné avec des vaccinations thérapeutiques, un traitement avec ce type de sucre permettrait peut-être d'induire des régressions tumorales chez un plus grand nombre de patients. L'équipe de Pierre van der Bruggen est en train de tester différents types de sucre qui pourraient être injectés chez des patients cancéreux et, in vitro, les premiers résultats sont prometteurs.

Plus d’informations

Demotte N, Stroobant V, Courtoy PJ, Van Der Smissen P, Colau D, Luescher IF, Hivroz C, Nicaise J, Squifflet JL, Mourad M, Godelaine D, Boon T, van der Bruggen P. Restoring the association of the T cell receptor with CD8 reverses anergy in human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Immunity, 2008, 28:414-24

Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde B, van der Bruggen P. Human T cell responses against melanoma. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 2006, 24:175-208.

The analysis of the T cell responses of melanoma patients vaccinated against tumor antigens has led to consider the possibility that the limiting factor for therapeutic success is not the intensity of the anti-vaccine response but the degree of anergy presented by intratumoral lymphocytes. We try to understand why tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are unable to kill tumor cells, and to find strategies to overcome this blockage. We have discovered a new type of anergy of human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, due to the presence of galectin-3, a lectin abundant in tumors, as it is corrected by galectin antagonists. We are further analyzing the mechanisms by which galectin antagonists reverse the impaired function and we look for agents that correct this function. A clinical trial combining anti-tumoral therapeutic vaccination and injection of galectin antagonists was launched in 2013 in clinical centers close to the de Duve Institute.

Previous work in our group: Identification of tumor antigens recognized by T cells

In the 1970s it became clear that T lymphocytes, a subset of the white blood cells, were the major effectors of tumor rejection in mice. In the 1980s, human anti-tumor cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTL) were isolated in vitro from the blood lymphocytes of cancer patients, mainly those who had melanoma. Most of these CTL were specific, i.e. they did not kill non-tumor cells. This suggested that they target a marker, or antigen, which is expressed exclusively on tumor cells. We started to study the anti-tumor CTL response of a metastatic melanoma patient and contributed to the definition of several distinct tumor antigens recognized by autologous CTL. In the early 1990s, we identified the gene coding for one of these antigens, and defined the antigenic peptide. This was the first description of a gene, MAGE-A1, coding for a human tumor antigen recognized by T lymphocytes.

Genes such as those of the MAGE family are expressed in many tumors and in male germline cells, but are silent in normal tissues. They are therefore referred to as “cancer-germline genes”. They encode tumor specific antigens, which have been used in therapeutic vaccination trials of cancer patients. A large set of additional cancer-germline genes have now been identified by different approaches, including purely genetic approaches. As a result, a vast number of sequences are known that can code for tumor-specific shared antigens. The identification of a larger set of antigenic peptides, which are presented by HLA class I and class II molecules and recognized on tumors by T lymphocytes, could be important for therapeutic vaccination trials of cancer patients and serve as tools for a reliable monitoring of the immune response of vaccinated patients. To that purpose, we have used various approaches that we have loosely named “reverse immunology”, because they use gene sequences as starting point.

Human tumor antigens recognized by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells are being defined at a regular pace worldwide. Together with colleagues at the de Duve Institute, we read the new publications and incorporate the newly defined antigens in a database accessible at http://cancerimmunity.org/peptide

Further reading

van der Bruggen P, Zhang Y, Chaux P, Stroobant V, Panichelli C, Schultz ES, Chapiro J, Van den Eynde BJ, Brasseur F, Boon T. 2002. Tumor-specific shared antigenic peptides recognized by human T cells. Immunological Reviews, 188: 51-64

van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, Boon T. 1991. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science, 254: 1643-1647

A mechanism causing anergy of CD8 and CD4 T lymphocytes

The identification of specific tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes on human cancer cells has elicited numerous clinical trials involving vaccination of tumor-bearing cancer patients with defined tumor antigens. These treatments have shown a low clinical efficacy. Among metastatic melanoma patients, about 5% show a complete or partial clinical response following vaccination, whereas an additional 10% show some evidence of tumor regression without clear clinical benefit. We believe that progress depends on unraveling the different blockages for efficient tumor destruction.

The tumors of the patients about to receive the vaccine, already contain T cells directed against tumor antigens. Presumably these T cells are exhausted and this impaired function is maintained by immunosuppressive factors present in the tumor. The T cell response observed in some vaccinated patients reinforce an hypothesis proposed by Thierry Boon and Pierre Coulie: anti-vaccine CTL are not the effectors that kill the tumor cells but their arrival at the tumor site containing exhausted anti-tumor CTL, generates conditions allowing the reawakening of the exhausted CTL and/or activation of new anti-tumor CTL clones, some of them contributing directly to tumor destruction. Accordingly, the difference between the responding and the non-responding vaccinated patients is not the intensity of their direct T cell response to the vaccine but the intensity of the immunosuppression inside the tumor. It is therefore important to know which immunosuppressive mechanisms operate in human tumors.

Dysfunction of T lymphocytes can be corrected by targeting galectins

CD8 T cell clones

CTL clones can be maintained in culture by stimulation every 1-2 weeks with cells presenting the antigen, in the presence of growth factors and EBV-B transformed cells as feeder cells. The functional status of CTL clones can be checked regularly by testing their capacity to lyse target cells expressing the relevant antigen and to produce cytokines upon antigenic stimulation, e.g. IFN-γ. Fluorescent HLA-peptide complexes –multivalent complexes of HLA molecules folded in the presence of the antigenic peptide and coupled to a fluorochrome– can be used to visualize antigen-specific CTL bearing the appropriate TCR (90). We observed that, compared with resting CTL collected 14 days after the last stimulation, recently activated CTL collected four days after stimulation have lost their capacity to bind HLA-tetramer complexes. They also secrete lower levels of cytokines upon a further antigenic stimulation (91). The decreased tetramer labeling and function was not due to a reduced surface expression of either the TCR or the CD8 co-receptor, which are both essential for tetramer labeling and activation of T lymphocytes. We decided therefore to examine by confocal microscopy the surface distribution of TCR and CD8 molecules on resting and recently activated T cells. TCR and CD8 molecules appeared to be co-localized on resting CTL, whereas TCR were segregated from CD8 molecules at the surface of recently activated CTL. These results were confirmed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), where interactions between two proteins can be estimated at a resolution of 10 nm.

Our hypothesis to explain the separation of TCR and the CD8 molecules at the cell surface of recently activated CTL is inspired by work from the group of Dennis and Demetriou (92, 93): N-glycosylated TCR molecules are clustered by extracellular galectin-3 and form glycoprotein-galectin lattices, which decrease the lateral mobility of TCR. In agreement with this hypothesis we observed that recently activated CTL, which were treated for 2 h with mM concentrations of galectin ligand N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc), secreted more IFN-γ upon antigenic stimulation. Moreover this short LacNAc treatment restored TCR-CD8 co-localization, as measured by FRET.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

We collected a large number of ascites samples from patients with various tumors, in particular ovarian and pancreatic carcinoma. We also collected samples of solid tumors, mostly melanoma. CD8 T lymphocytes were isolated from these samples and tested ex vivo ‑without prior in vitro expansion– for their capacity to secrete IFN-γ upon non-specific stimulation, using beads coated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. CD8 TIL from most of the samples secreted low levels of IFN-γ, in contrast with CD8 blood lymphocytes. Secretion of other cytokines by TIL was also low, e.g. IL-2 and TNF-α. These results are in line with the very few studies that have demonstrated dysfunction of human TIL (94-98).

Treating CD8 TIL for a few hours with mM concentrations of LacNAc increased by at least three times the secretion of IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF-α (99). This holds true for 80% of the samples tested so far. LacNAc-treated CD4 TIL were also able to secrete high amounts of IFN-γ upon stimulation. The cytotoxicity of CD8 TIL was tested in a redirected killing assay, where the targets were mouse cells decorated with anti-CD3 antibodies. The cytotoxicity of CD8 TIL was minimal compared to the cytotoxicity of blood CD8 T lymphocytes, but increased greatly after an overnight LacNAc treatment.

GCS-100, a modified citrus pectin, and GM-CT-01, a galactomannan extracted from guar beans, are polysaccharides that could bind to galectins and have already been injected in humans (100-102). A short treatment of CD8 TIL with mM concentrations of GCS-100 boosted their cytotoxicity to an efficiency level similar to LacNAc treatment. It also boosted the secretion of cytokines by either CD8 or CD4 TIL (99). Experiments with GM-CT-01 are ongoing and the results are very encouraging (manuscript in preparation).

LacNAc, GCS-100, and GM-CT-01 can interact with several galectins and therefore it is difficult to attribute the effect on TIL functions of these sugars to one galectin in particular. To understand which galectins were implicated, we searched for the presence of different extracellular galectins at the TIL surface. We detected both galectin-1 and galectin-3, but failed to detect galectin-8, -9 or MGL, a lectin implicated in the regulation of T-cell function (103). Treating TIL with anti-galectin-3 antibody B2C10 boosted IFN-γ secretion upon stimulation to levels similar to LacNAc or GCS-100 treatments (104). Because B2C10 was unable to detach galectin-1 while boosting TIL function, we concluded that detaching galectin-3 from TIL is sufficient to restore function, while not excluding a contribution of other galectins. We have so far failed to identify an anti-galectin-1 antibody able to detach galectin-1 from cells and are therefore unable to examine if galectin-1 also plays a role in TIL dysfunction.

How do galectins influence the distribution of T cell surface molecules?

Galectin-3 is an abundant lectin in many solid tumors and carcinomatous ascites. It can thus bind to surface glycoproteins of TIL. Glycoproteins often bear multiple copies of the sugar moieties that are recognized by galectins. The multivalent nature of galectin-glycan interactions results in high avidity in the range of 106 M−1, and allows the formation of galectin-glycoprotein lattices (reviewed elsewhere (105)). Similarly, lattices on TIL, formed by glycosylated surface receptors and extracellular galectin-3, would reduce the mobility of the former molecules, a fact that could explain the impaired function of TIL. The release of galectin-3 by soluble galectin ligands would restore the mobility of glycosylated surface receptors and boost IFN-γ secretion by TIL. Anti-galectin-3 antibody B2C10 should have a similar effect: this antibody binds to the N-terminal region of the galectin-3 and its rigid structure could prevent association of galectin-3 monomers mediated by the N-terminal region, thereby affecting the oligomerization of the lectin. Antibody B2C10 was shown to inhibit erythrocyte agglutination mediated by galectin-3 oligomerization (104).

The presence of galectin-glycoprotein lattices is in agreement with our observations with CTL clones and TIL. TCR and CD8 molecules are not co-localized on dysfunctional T cells and treating dysfunctional T cells with either an anti-galectin-3 antibody or galectin ligands detached galectin-3 from the T cell surface and restored the TCR-CD8 co-localization estimated by FRET (91, 99). Considering that HLA-peptide tetramer binding requires TCR and CD8 cooperation, the disorganization of galectin-glycoproteins lattices in the presence of galectin ligands could explain the recovery of HLA-peptide tetramer binding on dysfunctional CTL clones that were treated with LacNAc (91).

A number of publications suggest that several human T cell surface glycoproteins can be linked together by galectins and form lattices. Human TCR α-chain, in contrast to the β-chain, has been shown to harbor complex N-glycans, the major natural ligands for galectin-3 (106, 107). The removal of an N-glycosylation site from a human TCR α-chain was reported to result in increased avidity of T cells grafted with the gene encoding the modified TCR (108). Galectin-3 was reported to bind to CD45, CD29, CD43, and CD71 (109), and galectin-1 to CD45, CD7 and CD43 (110). Galectin-1/CD7 ligation was shown to induce apoptosis of CD4 T lymphocytes (111). It has also been shown by immunoprecipitation that galectin-3 binds to CD45 and that galectin-3 influences the CD45 partition to microdomains containing the TCR (112). Interestingly, CD45-TCR proximity is known to negatively regulate the TCR signaling cascade (113).

Glycosylation changes at the T cell surface

To explain that galectin-3, alone or together with galectin-1, inhibits functions of recently activated T cells, we surmised that the recently activated T cells, compared to resting T cells, harbor a set of glycans that are either more numerous or better ligands for galectin-3. We stimulated resting CTL in the presence of swainsonine that inhibits α-mannosidase II involved in the N-glycosylation pathway. Compared to untreated cells, cells stimulated in the presence of swainsonine showed on day 4 a better TCR-CD8 co-localization and a higher ability to release IFN-γ upon antigenic stimulation (91).

We also characterized global changes in surface N- and O-glycans on two human CTL clones that were collected either in a resting state, 14 days after antigenic stimulation, or in a recently activated state, four days after antigenic stimulation. Applying ultra-sensitive MALDI-TOF-MS, combined with various glycosidase digestions and GC-MS linkage analyses, we made two novel observations.

Firstly, the N-glycome of recently activated cells versus resting cells consists of longer LacNAc chains, of which a portion contains more than four LacNAc moieties (poly-LacNAc). Secondly, it contains more multi-antennary N-glycans (114). Interestingly, our results showed that the above poly-LacNAc chains appeared to be equally distributed on all available N-glycan branches and not selectively enriched on a specific branch. In contrast, murine T cells are poor in tri- and tetra-antennary poly-LacNAc glycans (115). This difference could potentially explain the crucial role in mice of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V (Mgat5), an enzyme essential for the generation of complex tetra-antennary N-glycan, as T cells from mice lacking Mgat5, compared to their wildtype counterparts, are more sensitive to activation and have reduced poly-LacNAc motives (92). The glycome modifications observed on human CTL clones upon activation are expected to increase the number of galectin-3 natural ligands, but also the number of galectin-1 ligands, and favor lattices that could reduce the mobility of surface glycoproteins, as the affinity of both galectins was reported to be much higher when repeated LacNAc units are present (116).

We also observed that recently activated CTL clones exhibited a lower abundance of terminal a2,6-linked NeuAc residues than resting CTL (114). Galectin-1 binds to terminal LacNAc units, even if they are decorated with a2,3-linked NeuAc. On the contrary, galectin-1 binding is blocked by the presence of terminal a2,6-linked NeuAc (88, 110, 111, 117, 118). Our glycome analyses suggest therefore that more galectin-1 natural ligands are presented on recently activated CTL versus resting CTL.

All together, the results of our glycome analyses of CTL clones combined with the fact that functions of both CTL clones and TIL can be boosted by galectin ligands, support our working hypothesis: TIL are in permanent contact with tumor cells and have been stimulated by antigen recently. The resulting activation of T cells modifies the expression profiles of enzymes of the N-glycosylation pathway, increasing the expression of N-glycans at the T cell surface. Considering the high abundance of extracellular galectins in tumors, secreted by tumor cells and macrophages, this could favor the formation of galectin-glycoprotein lattices and therefore the dysfunction of some TIL.

Towards a clinical trial combining vaccination and galectin-binding polysaccharides

As described above, treating TIL with modified citrus pectin GCS-100 improved their ability to secrete IFN-γ upon stimulation. We decided therefore to test the therapeutic effect of GCS-100 in tumor-bearing mice. We injected 40 mice subcutaneously in the flank with 2x106 P815 mastocytoma cells. On day 4, half of the animals were vaccinated with an adenovirus encoding P815 tumor antigen P1A (5). Therapeutic vaccination has thus far proven ineffective at inducing tumor rejection in tumor-bearing mice (Catherine Uyttenhove & Guy Warnier, personal communication). On day 10, treatments with either PBS or GCS-100 were initiated three times a week. Three weeks later, the tumor had become undetectable in six out of the ten vaccinated mice treated with GCS-100, of which five were still alive after another three months. Control mice that received only the vaccine died. In non-vaccinated mice, the polysaccharide had no visible effect by itself. These results suggest that a combination of galectin-3 ligands and therapeutic vaccination may induce more effective tumor regression in cancer patients than vaccination alone. Setting up a clinical trial combining anti-tumoral vaccination and GCS-100 was impossible because the pharmaceutical company that produced the GCS-100 declared bankruptcy.

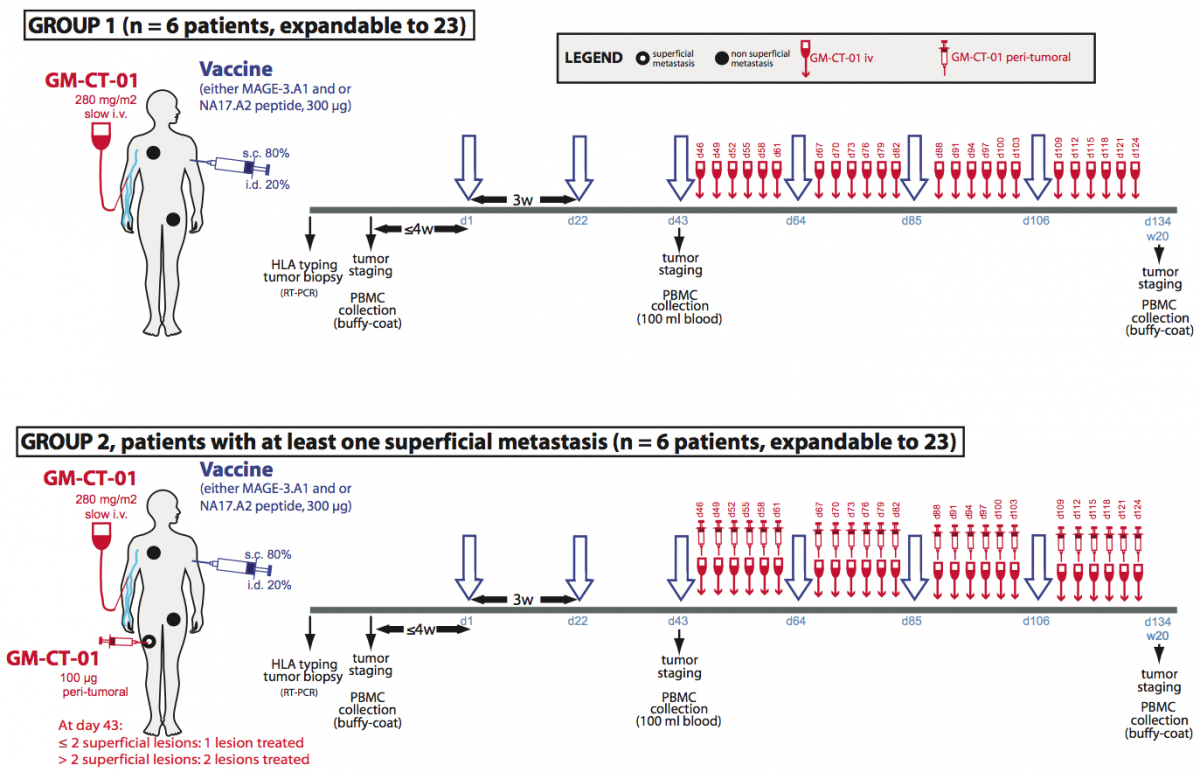

GM-CT-01, a galactomannan derived from guar gum, has been shown to bind to galectin-1 (119), and to increase the anti-tumor activity of chemotherapy drug 5-fluorouracil. It was previously injected in patients with solid tumors without major side effects (120). We have treated TIL samples with GM-CT-01 and the first results are encouraging. We therefore will launch a Phase I/II clinical trial combining peptide vaccination associated with intravenous injections of GM-CT-01 in patients with advanced melanoma (Fig.1). Patients will receive sequential vaccinations with one or two peptides, MAGE-3.A1 and NA17.A2, matching the tumor antigens expressed by their tumor. Their formulation and schedule of vaccination (timing, dose, route of administration) will be similar to previous trials with these peptides (15, 20, 21). GM-CT-01 will be administered systemically by repeated intravenous infusions, in order to ensure a prolonged effect on tumor-associated lymphocytes. The treatment dose matches the total cumulative dose in previous GM-CT-01 treatment schedules (120). For selected patients with cutaneous or subcutaneous metastases, in addition to systemic GM-CT-01, small amounts of this drug will be injected close to metastases, to increase local concentration of the drug.

Figure 1. Treatment plan of the clinical trial involving GM-CT-01.

Treatment allocation: Patients will be divided in two treatment arms. Both will run in parallel. Patients with at least one measurable lesion will be assigned to group 1 and will receive the following treatment: peptide vaccinations and systemic GM-CT-01 injections. Patients with at least one measurable and at least one superficial metastasis will be assigned in priority to group 2 and will receive the following treatment: peptide vaccinations, systemic GM-CT-01 administrations and peri-tumoral administration of GM-CT-01 in one or two superficial metastases.

Human tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes show impaired IFN-γ secretion

Both human CD8 and CD4 tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes (TIL) were isolated from tumor ascites or solid tumors and compared with T lymphocytes from blood donors. TIL secrete low levels of INF-γ and other cytokines upon non-specific stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. TCR were observed to be distant from the co-receptors on the cell surface of TIL, either CD8 or CD4, whereas TCR and the co-receptors co-localized on blood T lymphocytes.

TCR and CD8 do not co-localize on CD8 T cells with impaired functions (in collaboration with P. Vandersmissen and P. Courtoy, PICT/SSS)

Reversing the anergy of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes with galectin antagonists

We have attributed the decreased IFN-γ secretion to a reduced mobility of T cell receptors upon trapping in a lattice of glycoproteins clustered by extracellular galectin-3. Indeed, we have shown that treatment of TIL with N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc), a galectin antagonist, restored this secretion.

Treatment of tumor-infitrating lymphocytes with a galectin antagonist reverses

Our working hypothesis is that TIL have been stimulated by antigen chronically, and that the resulting activation of T cells could modify the expression of enzymes of the N-glycosylation pathway, as shown for murine T cells. The chronically activated TIL, compared to resting T cells, could thus express surface glycoproteins decorated with a set of glycans that are either more numerous or better antagonists for galectin-3. Galectin-3 is an abundant lectin in many solid tumors and carcinomatous ascites, and can thus bind to surface glycoproteins of TIL and form lattices that would thereby reduce TCR mobility. This could explain the impaired function of TIL. The release of galectin-3 by soluble competitor antagonists would restore TCR mobility and boost IFN-γ secretion by TIL. We recently strengthened this hypothesis by showing that both CD4 and CD8 TIL that were treated with an anti-galectin-3 antibody, which could disorganize lattice formation, had an increased IFN-γ secretion compared to untreated cells.

Towards a clinical trial combining vaccination and galectin-binding polysaccharides

Galectin competitor antagonists, e.g. disaccharides LacNAc, are rapidly eliminated in urine, preventing their use in vivo. We recently found that a plant-derived polysaccharide, currently in clinical development, detached galectin-3 from TIL and boosted their IFN-γ secretion. Importantly, we observed that not only CD8+ TIL but also CD4+ TIL that were treated with this polysaccharide secreted more IFN-γ upon ex vivo re-stimulation. In tumor-bearing mice vaccinated with a tumor antigen, injections of this polysaccharide led to tumor rejection in half of the mice, whereas all control mice died. In non-vaccinated mice, the polysaccharide had no effect by itself. These results suggest that a combination of galectin-3 antagonists and therapeutic vaccination may induce more tumor regressions in cancer patients than vaccination alone. Translation of these results to the clinic was unfortunately impossible because the company producing this polysaccharide got bankrupted. We recently identified another plant-derived polysaccharide that binds to galectins and was already used in combination with chemotherapy in phase II clinical trials in colorectal cancer patients. This compound was as effective as LacNAc in boosting the secretion of IFN-γ by treated TIL. A clinical trial with this new compound, in combination with anti-tumoral vaccination was launched in 2013 in clinical centers close to the de Duve Institute. We are currently trying to understand the very early activation events that are defective in TIL.

Further reading

Antonopoulos A, Demotte N, Stroobant V, Haslam SM, van der Bruggen P, Dell A. 2012. Loss of effector function of human cytolytic T lymphocytes is accompanied by major alterations in N- and O-glycosylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287: 11240-11251

Demotte N, Wieërs G, Van Der Smissen P, Moser M, Schmidt CW, Thielemans K, Squifflet J-L, Weynand B, Carrasco J, Lurquin C, Courtoy PJ, van der Bruggen P. 2010. A galectin-3 ligand corrects the impaired function of human CD4 and CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and favors tumor rejection in mice. Cancer Research, 70: 7476-7488

Demotte N, Stroobant V, Courtoy PJ, Van der Smissen P, Colau D, Luescher IF, Hivroz C, Nicaise J, Squifflet J-L, Mourad M, Godelaine D, Boon T, van der Bruggen P. 2008. Restoring the association of the T cell receptor with CD8 reverses anergy in human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Immunity, 28: 414-424

Demotte N, Colau D, Ottaviani S, Godelaine D, Van Pel A, Boon T, van der Bruggen P. 2002. A reversible functional defect of CD8+ T lymphocytes involving loss of tetramer labeling. European Journal of Immunology, 32: 1688-1697

Petit AE, Demotte N, Scheid B, Wildmann C, Bigirimana R, Gordon-Alonso M, Carrasco J, Valitutti S, Godelaine D, van der Bruggen P.

Nat Commun. 2016; 7:12242.

Demotte N, Bigirimana R, Wieërs G, Stroobant V, Squifflet JL, Carrasco J, Thielemans K, Baurain JF, Van Der Smissen P, Courtoy PJ, van der Bruggen P.

Clin Cancer Res. 2014; 20(7):1823-33.

Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P, Boon T.

Nat Rev Cancer. 2014; 14(2):135-46.

Demotte N, Wieërs G, Van Der Smissen P, Moser M, Schmidt C, Thielemans K, Squifflet JL, Weynand B, Carrasco J, Lurquin C, Courtoy PJ, van der Bruggen P.

Cancer Res. 2010; 70(19):7476-88.

François V, Ottaviani S, Renkvist N, Stockis J, Schuler G, Thielemans K, Colau D, Marchand M, Boon T, Lucas S, van der Bruggen P.

Cancer Res. 2009; 69(10):4335-45.

Demotte N, Stroobant V, Courtoy PJ, Van Der Smissen P, Colau D, Luescher IF, Hivroz C, Nicaise J, Squifflet JL, Mourad M, Godelaine D, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

Immunity. 2008; 28(3):414-24.

Annu Rev Immunol. 2006; 24:175-208. Review.

Zhang Y, Sun Z, Nicolay H, Meyer RG, Renkvist N, Stroobant V, Corthals J, Carrasco J, Eggermont AM, Marchand M, Thielemans K, Wölfel T, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

J Immunol. 2005; 174(4):2404-11.

Demotte N, Colau D, Ottaviani S, Godelaine D, Van Pel A, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

Eur J Immunol. 2002; 32(6):1688-97.

Schultz ES, Chapiro J, Lurquin C, Claverol S, Burlet-Schiltz O, Warnier G, Russo V, Morel S, Lévy F, Boon T, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P.

J Exp Med. 2002; 195(4):391-9.

Schultz ES, Lethé B, Cambiaso CL, Van Snick J, Chaux P, Corthals J, Heirman C, Thielemans K, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

Cancer Res. 2000; 60(22):6272-5.

Chaux P, Luiten R, Demotte N, Vantomme V, Stroobant V, Traversari C, Russo V, Schultz E, Cornelis GR, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

J Immunol. 1999; 163(5):2928-36.

Chaux P, Vantomme V, Stroobant V, Thielemans K, Corthals J, Luiten R, Eggermont AM, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

J Exp Med. 1999; 189(5):767-78.

Mandruzzato S, Brasseur F, Andry G, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

J Exp Med. 1997; 186(5):785-93.

Boël P, Wildmann C, Sensi ML, Brasseur R, Renauld JC, Coulie P, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

Immunity. 1995; 2(2):167-75.

van der Bruggen P, Bastin J, Gajewski T, Coulie PG, Boël P, De Smet C, Traversari C, Townsend A, Boon T.

Eur J Immunol. 1994; 24(12):3038-43.

van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, Boon T.

Science. 1991; 254(5038):1643-7.

DYSFONCTIONNEMENT DES LYMPHOCYTES T DANS LES TUMEURS