We proberen te begrijpen waarom T-lymfocyten die in tumoren infiltreren niet in staat zijn om de tumorcellen te doden. Daarnaast proberen we klinische wegen te vinden om deze blokkade te overwinnen. Zo hebben we ontdekt dat het falen van de lymfocyten die in menselijke tumoren infiltreren te wijten kan zijn aan de aanwezigheid van galectine-3, een lectine dat overvloedig aanwezig is in de tumoren.

T-lymfocyten die kankercellen doden

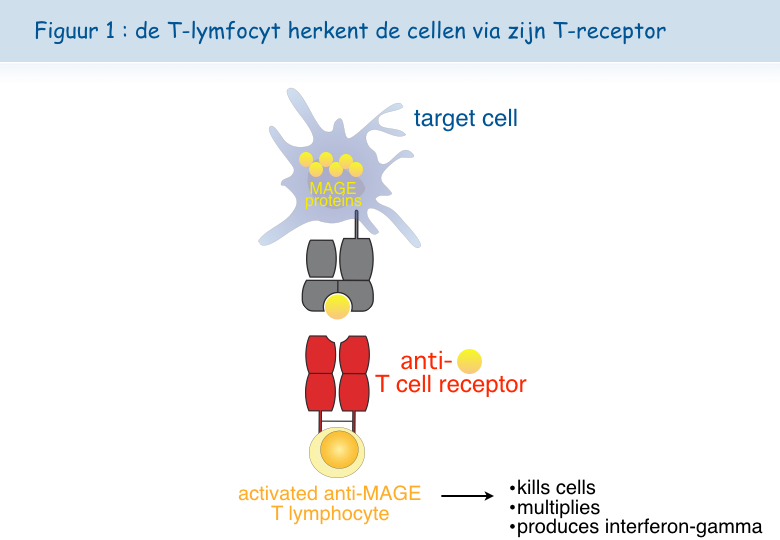

Dat ons immuunsysteem ons zou kunnen verlossen van bepaalde kankers is een droom waarvan de experimentele basis al dateert uit de jaren 40. Muizen die geopereerd werden aan een tumor waren in staat om cellen van dezelfde tumor – na toediening via injectie - te elimineren. Cellen van een andere tumor konden ze dan weer niet elimineren. Dit wees op een interventie van het immuunsysteem. Het immuunsysteem werkt met speciale witte bloedcellen, T-lymfocyten geheten. T-lymfocyten beschikken over receptoren die lichaamsvreemde moleculaire structuren (antigenen genoemd) kunnen herkennen. We beschikken over tientallen miljoenen verschillende T-lymfocyten, allemaal drager van één type receptor dat een specifiek antigen kan herkennen. De herkenning van het antigen door de T-lymfocyt leidt tot de vermenigvuldiging en activatie van de lymfocyt. Sommige worden cytolytische lymfocyten, die in staat zijn om de cel waarop ze hun antigen herkennen uiteen te laten spatten en om vervolgens moleculen te produceren die dienst doen als boodschapper voor andere cellen. Een van deze boodschappers is het gamma-interferon.

De ontdekking van antigenen van tumoren

De T-lymfocyten kunnen ons genezen van virale infecties, doordat geïnfecteerde cellen virale antigenen dragen. Tot een twintigtal jaar geleden wist niemand of ook menselijke tumoren over specifieke antigenen beschikken en dus of menselijke T-lymfocyten een onderscheid kunnen maken tussen tumorcellen en normale cellen. Vandaag bestaat er geen enkele twijfel meer over dat de meeste menselijke kankercellen specifieke antigenen hebben. Het De Duve Instituut heeft een doorslaggevende rol gespeeld bij het aantonen van dit concept met de ontdekking van de eerste tumorale antigenen door het team van Thierry Boon. Pierre van der Bruggen en Catia Traversari speelden een voortrekkersrol. Inmiddels zijn al tientallen antigenen gekend, die herkend worden door cytolytische T-lymfocyten, maar er blijven er nog heel wat te ontdekken. Sommige van deze antigenen zijn uitstekende kandidaten voor de ontwikkeling van een therapie gebaseerd op de activatie van de tumorbestrijdende T-lymfocyten. De aanwezigheid van tumorale antigenen komt voort uit de expressie van bepaalde genen, waaronder een specifieke groep genen die MAGE wordt genoemd. Deze genen worden uitgedrukt in heel wat tumoren, maar niet in de normale weefsels (Figuur 1).

De MAGE-antigenen zijn aanwezig op heel wat verschillende kankers. Dat maakt het mogelijk om bij verschillende patiënten hetzelfde therapeutische vaccin te gebruiken. We hebben het hier over een therapeutisch vaccin in tegenstelling tot preventieve vaccins.

Therapeutische vaccinatie tegen tumoren

De eerste therapeutische vaccinaties met MAGE-antigenen gingen van start in 1994 bij patiënten met een melanoom. Van alle gevaccineerde patiënten vertoonde 15% een significante afname (regressie) van de kanker, terwijl de frequentie van spontane regressie – dus zonder behandeling of vaccin - bij een metastatisch melanoom op minder dan 0,5% geschat wordt. De soms volledige en duurzame regressies werden verkregen zonder enige bijwerking, wat ons een doorslaggevend voordeel lijkt ten opzichte van de klassieke kankerbehandelingen, zoals chemotherapie.

De essentie voor de toekomst bestaat erin te begrijpen waarom de therapeutische vaccinaties in de meeste gevallen mislukken. Is het ons bij die patiënten niet gelukt om een reactie van de lymfocyten uit te lokken? Is hun tumor resistent tegen de aanval van het immuunsysteem? En in beide gevallen, waarom?

De T-lymfocyten die we terugvinden in de tumoren zijn uitgeput

In de beginfase van ons klinisch programma dachten we dat het immuunsysteem van een kankerpatiënt “in slapende toestand” bleef bij de aanwezigheid van de antigenen die door de tumor werden uitgedrukt. Een vaccin met de juiste ingrediënten zou leiden tot sterke reacties van de T-lymfocyten, die de kankercellen dan zouden vernietigen.

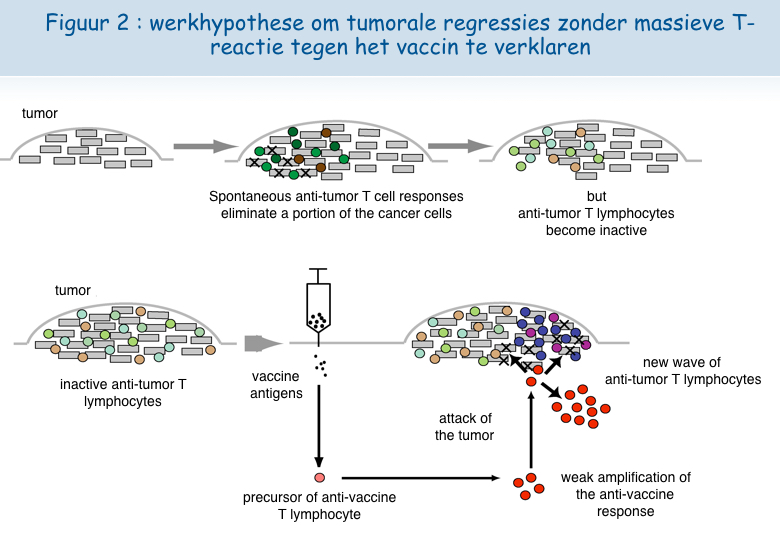

Verschillende observaties door het team van Pierre Coulie in het De Duve Institute en door het team van Thierry Boon liggen aan de basis van een ander scenario als verklaring voor de tumorregressie na vaccinatie. Patiënten met een metastatisch melanoom ontwikkelen spontane immuunreacties tegen bepaalde antigenen op de tumorcellen. Tumorbestrijdende lymfocyten concentreren zich in de metastases, maar kunnen waarschijnlijk niet langer doeltreffend optreden omdat de tumor een verdedigingsmechanisme ontwikkelt. Bij sommige patiënten zou een klein aantal door het vaccin geactiveerde T-lymfocyten in de tumor migreren en er zo, door een onbekend mechanisme, in slagen om andere tumorbestrijdende lymfocyten te (her)activeren. Deze kunnen zich vervolgens vermenigvuldigen en de kankercellen vernietigen (Figuur 2).

Een nieuw uitputtingsmechanisme van de lymfocyten

Analyse van in het laboratorium gekweekte lymfocyten

Uit verschillende onderzoeken blijkt dat de lymfocyten die in tumoren infiltreren niet correct werken. We spreken dan van dysfunctie van de T-lymfocyten.

Onderzoekers van het team van Pierre van der Bruggen hebben een nieuw dysfunctiemechanisme van de menselijke T-lymfocyten geïdentificeerd en hebben methodes ontdekt om deze dysfunctie te corrigeren. In eerste instantie hebben ze vastgesteld dat de meeste cytolytische T-lymfocyten, na contact met cellen met het antigen, gedurende enkele dagen hun vermogen verliezen om die cellen met het antigen te doden en om het gamma-interferon af te scheiden.

Verschillende experimentele benaderingen zijn ingezet om te proberen deze dysfunctie te begrijpen.

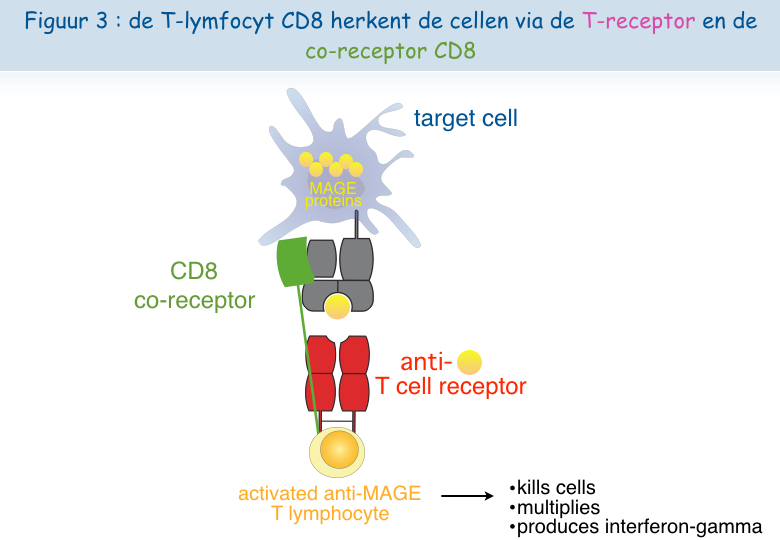

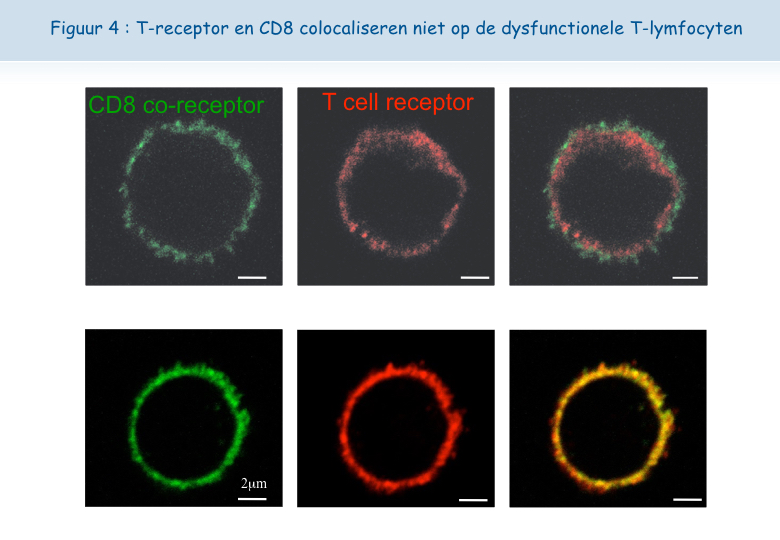

Een cytolytische T-lymfocyt heeft minstens twee receptoren nodig om het antigen te kunnen herkennen en om geactiveerd te worden: TCR en CD8 (Figuur 3). Dankzij een nieuwe microscoop van het De Duve Instituut kon vastgesteld worden dat deze twee receptoren dicht bij elkaar liggen (gecolocaliseerd) op het oppervlak van functionele lymfocyten, maar niet op het oppervlak van dysfunctionele lymfocyten (Figuur 4). Aan dit onderzoek hebben Pierre Courtoy en Patrick Van Der Smissen van de afdeling Celbiologie hun expertise bijgedragen.

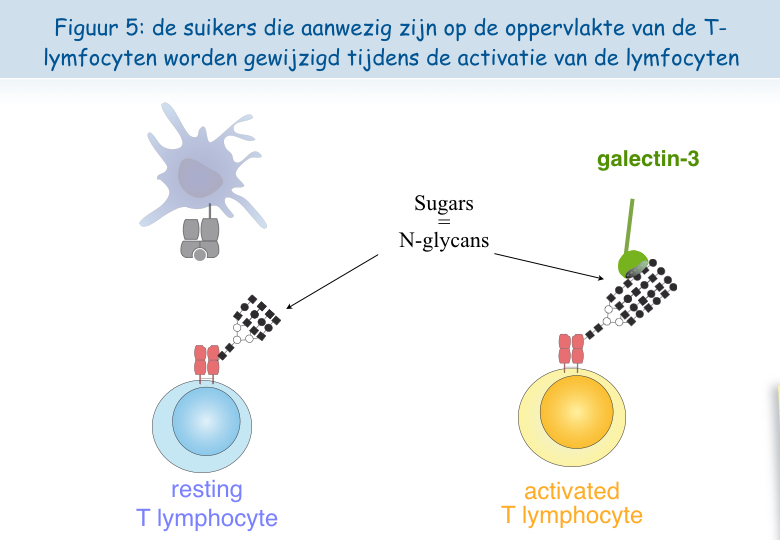

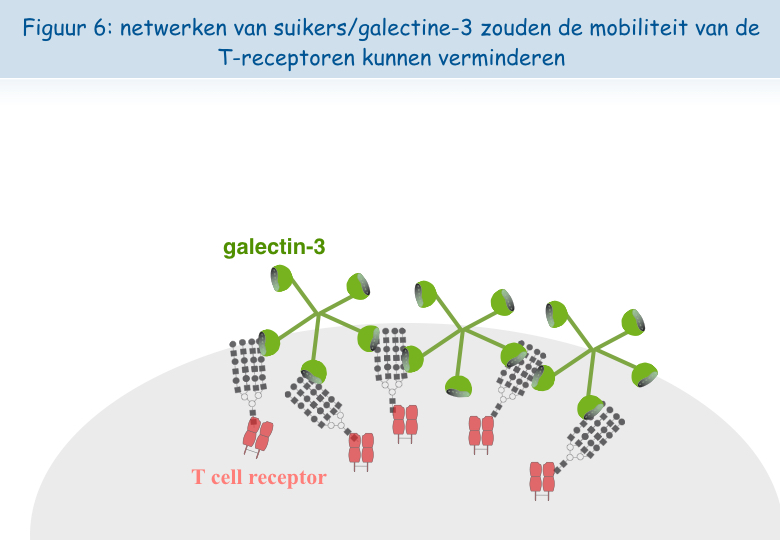

Het lijkt erop dat, wanneer de lymfocyten zich te vaak in aanwezigheid van het antigen bevinden, de TCR-receptor zich laadt met “suikers”. Een molecuul genaamd galectine-3, hecht zich vast aan deze suikers en verbindt de TCR-receptoren met elkaar. Zo verliezen deze hun mobiliteit en kunnen ze niet langer in interactie treden met de andere receptor, CD8 (Figuren 5, 6 & 7).

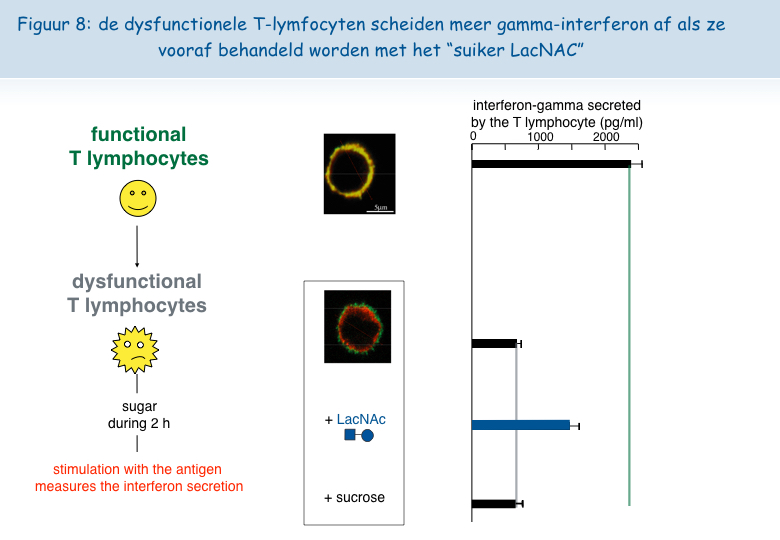

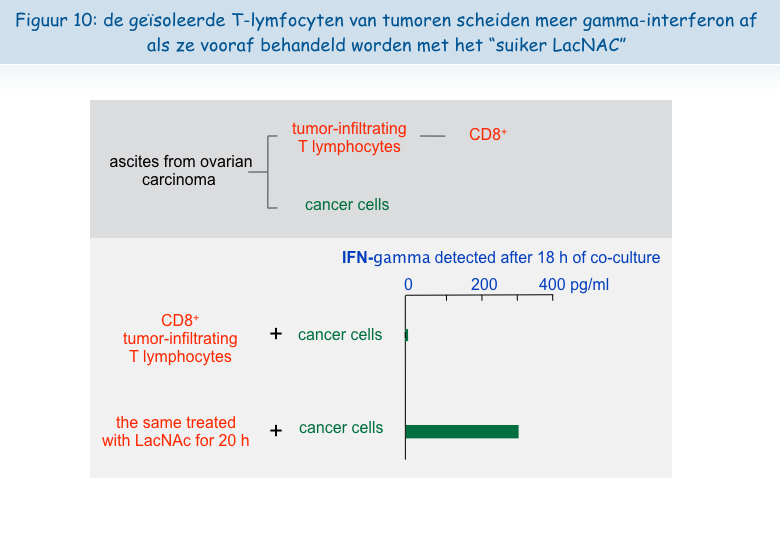

Om deze hypothese te testen, werd bij in het laboratorium gekweekte dysfunctionele T-lymfocyten een suiker toegevoegd dat zich hecht aan het galectine-3, het zogeheten LacNAc. Een behandeling van twee uur met LacNAc maakte het mogelijk om een groot deel van de colocalisatie van de TCR en CD8 receptoren te recupereren. De T-lymfocyten die behandeld werden met LacNAc waren na een stimulering met het antigen ook opnieuw in staat om het interferon-g af te scheiden (Figuur 8).

Analyse van de lymfocyten in tumoren van patienten

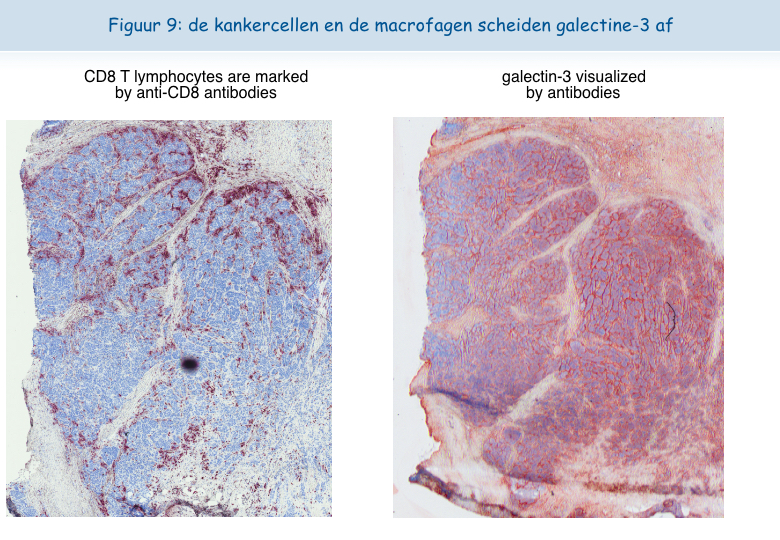

We vinden heel vaak grote hoeveelheden galectine-3 in de tumoren terug (Figuur 9).

Het was verleidelijk te denken dat - net als de in het laboratorium gekweekte T-lymfocyten - T-lymfocyten in tumoren dysfunctioneel zijn door de aanwezigheid van galectine-3. Dankzij de samenwerking met artsen van het Brusselse ziekenhuis Sint-Lucas zijn we erin geslaagd menselijke T-lymfocyten uit tumoren te isoleren. Op het oppervlak van deze T-lymfocyten waren de TCR en de CD8 receptoren niet gecolocaliseerd. De lymfocyten bleken niet in staat om het gamma-interferon uit te scheiden na een stimulatie met tumorcellen. Uit deze resultaten bleek duidelijk dat de dysfunctie van de lymfocyten in de tumoren gekoppeld is aan een afwezigheid van colocalisatie van de TCR en de CD8 receptoren.

De uitgeputte T-lymfocyten wakker maken

De volgende observatie was de belangrijkste: het was mogelijk om de functies van de geisoleerde T-lymfocyten wakker te maken. Na een nacht incubatie in aanwezigheid van LacNAc (de suiker die zich hecht aan galectine-3) hadden de lymfocyten de colocalisatie van TCR en CD8 gerecupereerd, evenals hun vermogen om het gamma-interferon af te scheiden (Figuur 10).

Deze ex vivo verkregen resultaten stellen ons in staat om te suggereren dat het injecteren van LacNAc of andere antagonisten van galectine in tumoren de functies van de T-lymfocyten tenminste tijdelijk zou kunnen herstellen om zo gunstige omstandigheden te creëren voor een doeltreffende tumorbestrijdende reactie. In combinatie met therapeutische vaccins zou een behandeling met dit type suiker kunnen leiden tot tumorale regressies bij een groter aantal patiënten. Het team van Pierre van der Bruggen is bezig met het testen van verschillende types suiker die bij kankerpatiënten geïnjecteerd zouden kunnen worden en de eerste resultaten in vitro zijn alvast veelbelovend.

Meer informatie

Demotte N, Stroobant V, Courtoy PJ, Van Der Smissen P, Colau D, Luescher IF, Hivroz C, Nicaise J, Squifflet JL, Mourad M, Godelaine D, Boon T, van der Bruggen P. Restoring the association of the T cell receptor with CD8 reverses anergy in human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Immunity, 2008, 28:414-24

Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde B, van der Bruggen P. Human T cell responses against melanoma. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 2006, 24:175-208.

The analysis of the T cell responses of melanoma patients vaccinated against tumor antigens has led to consider the possibility that the limiting factor for therapeutic success is not the intensity of the anti-vaccine response but the degree of anergy presented by intratumoral lymphocytes. We try to understand why tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are unable to kill tumor cells, and to find strategies to overcome this blockage. We have discovered a new type of anergy of human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, due to the presence of galectin-3, a lectin abundant in tumors, as it is corrected by galectin antagonists. We are further analyzing the mechanisms by which galectin antagonists reverse the impaired function and we look for agents that correct this function. A clinical trial combining anti-tumoral therapeutic vaccination and injection of galectin antagonists was launched in 2013 in clinical centers close to the de Duve Institute.

Previous work in our group: Identification of tumor antigens recognized by T cells

In the 1970s it became clear that T lymphocytes, a subset of the white blood cells, were the major effectors of tumor rejection in mice. In the 1980s, human anti-tumor cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTL) were isolated in vitro from the blood lymphocytes of cancer patients, mainly those who had melanoma. Most of these CTL were specific, i.e. they did not kill non-tumor cells. This suggested that they target a marker, or antigen, which is expressed exclusively on tumor cells. We started to study the anti-tumor CTL response of a metastatic melanoma patient and contributed to the definition of several distinct tumor antigens recognized by autologous CTL. In the early 1990s, we identified the gene coding for one of these antigens, and defined the antigenic peptide. This was the first description of a gene, MAGE-A1, coding for a human tumor antigen recognized by T lymphocytes.

Genes such as those of the MAGE family are expressed in many tumors and in male germline cells, but are silent in normal tissues. They are therefore referred to as “cancer-germline genes”. They encode tumor specific antigens, which have been used in therapeutic vaccination trials of cancer patients. A large set of additional cancer-germline genes have now been identified by different approaches, including purely genetic approaches. As a result, a vast number of sequences are known that can code for tumor-specific shared antigens. The identification of a larger set of antigenic peptides, which are presented by HLA class I and class II molecules and recognized on tumors by T lymphocytes, could be important for therapeutic vaccination trials of cancer patients and serve as tools for a reliable monitoring of the immune response of vaccinated patients. To that purpose, we have used various approaches that we have loosely named “reverse immunology”, because they use gene sequences as starting point.

Human tumor antigens recognized by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells are being defined at a regular pace worldwide. Together with colleagues at the de Duve Institute, we read the new publications and incorporate the newly defined antigens in a database accessible at http://cancerimmunity.org/peptide

Further reading

van der Bruggen P, Zhang Y, Chaux P, Stroobant V, Panichelli C, Schultz ES, Chapiro J, Van den Eynde BJ, Brasseur F, Boon T. 2002. Tumor-specific shared antigenic peptides recognized by human T cells. Immunological Reviews, 188: 51-64

van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, Boon T. 1991. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science, 254: 1643-1647

A mechanism causing anergy of CD8 and CD4 T lymphocytes

The identification of specific tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes on human cancer cells has elicited numerous clinical trials involving vaccination of tumor-bearing cancer patients with defined tumor antigens. These treatments have shown a low clinical efficacy. Among metastatic melanoma patients, about 5% show a complete or partial clinical response following vaccination, whereas an additional 10% show some evidence of tumor regression without clear clinical benefit. We believe that progress depends on unraveling the different blockages for efficient tumor destruction.

The tumors of the patients about to receive the vaccine, already contain T cells directed against tumor antigens. Presumably these T cells are exhausted and this impaired function is maintained by immunosuppressive factors present in the tumor. The T cell response observed in some vaccinated patients reinforce an hypothesis proposed by Thierry Boon and Pierre Coulie: anti-vaccine CTL are not the effectors that kill the tumor cells but their arrival at the tumor site containing exhausted anti-tumor CTL, generates conditions allowing the reawakening of the exhausted CTL and/or activation of new anti-tumor CTL clones, some of them contributing directly to tumor destruction. Accordingly, the difference between the responding and the non-responding vaccinated patients is not the intensity of their direct T cell response to the vaccine but the intensity of the immunosuppression inside the tumor. It is therefore important to know which immunosuppressive mechanisms operate in human tumors.

Dysfunction of T lymphocytes can be corrected by targeting galectins

CD8 T cell clones

CTL clones can be maintained in culture by stimulation every 1-2 weeks with cells presenting the antigen, in the presence of growth factors and EBV-B transformed cells as feeder cells. The functional status of CTL clones can be checked regularly by testing their capacity to lyse target cells expressing the relevant antigen and to produce cytokines upon antigenic stimulation, e.g. IFN-γ. Fluorescent HLA-peptide complexes –multivalent complexes of HLA molecules folded in the presence of the antigenic peptide and coupled to a fluorochrome– can be used to visualize antigen-specific CTL bearing the appropriate TCR (90). We observed that, compared with resting CTL collected 14 days after the last stimulation, recently activated CTL collected four days after stimulation have lost their capacity to bind HLA-tetramer complexes. They also secrete lower levels of cytokines upon a further antigenic stimulation (91). The decreased tetramer labeling and function was not due to a reduced surface expression of either the TCR or the CD8 co-receptor, which are both essential for tetramer labeling and activation of T lymphocytes. We decided therefore to examine by confocal microscopy the surface distribution of TCR and CD8 molecules on resting and recently activated T cells. TCR and CD8 molecules appeared to be co-localized on resting CTL, whereas TCR were segregated from CD8 molecules at the surface of recently activated CTL. These results were confirmed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), where interactions between two proteins can be estimated at a resolution of 10 nm.

Our hypothesis to explain the separation of TCR and the CD8 molecules at the cell surface of recently activated CTL is inspired by work from the group of Dennis and Demetriou (92, 93): N-glycosylated TCR molecules are clustered by extracellular galectin-3 and form glycoprotein-galectin lattices, which decrease the lateral mobility of TCR. In agreement with this hypothesis we observed that recently activated CTL, which were treated for 2 h with mM concentrations of galectin ligand N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc), secreted more IFN-γ upon antigenic stimulation. Moreover this short LacNAc treatment restored TCR-CD8 co-localization, as measured by FRET.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

We collected a large number of ascites samples from patients with various tumors, in particular ovarian and pancreatic carcinoma. We also collected samples of solid tumors, mostly melanoma. CD8 T lymphocytes were isolated from these samples and tested ex vivo ‑without prior in vitro expansion– for their capacity to secrete IFN-γ upon non-specific stimulation, using beads coated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. CD8 TIL from most of the samples secreted low levels of IFN-γ, in contrast with CD8 blood lymphocytes. Secretion of other cytokines by TIL was also low, e.g. IL-2 and TNF-α. These results are in line with the very few studies that have demonstrated dysfunction of human TIL (94-98).

Treating CD8 TIL for a few hours with mM concentrations of LacNAc increased by at least three times the secretion of IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF-α (99). This holds true for 80% of the samples tested so far. LacNAc-treated CD4 TIL were also able to secrete high amounts of IFN-γ upon stimulation. The cytotoxicity of CD8 TIL was tested in a redirected killing assay, where the targets were mouse cells decorated with anti-CD3 antibodies. The cytotoxicity of CD8 TIL was minimal compared to the cytotoxicity of blood CD8 T lymphocytes, but increased greatly after an overnight LacNAc treatment.

GCS-100, a modified citrus pectin, and GM-CT-01, a galactomannan extracted from guar beans, are polysaccharides that could bind to galectins and have already been injected in humans (100-102). A short treatment of CD8 TIL with mM concentrations of GCS-100 boosted their cytotoxicity to an efficiency level similar to LacNAc treatment. It also boosted the secretion of cytokines by either CD8 or CD4 TIL (99). Experiments with GM-CT-01 are ongoing and the results are very encouraging (manuscript in preparation).

LacNAc, GCS-100, and GM-CT-01 can interact with several galectins and therefore it is difficult to attribute the effect on TIL functions of these sugars to one galectin in particular. To understand which galectins were implicated, we searched for the presence of different extracellular galectins at the TIL surface. We detected both galectin-1 and galectin-3, but failed to detect galectin-8, -9 or MGL, a lectin implicated in the regulation of T-cell function (103). Treating TIL with anti-galectin-3 antibody B2C10 boosted IFN-γ secretion upon stimulation to levels similar to LacNAc or GCS-100 treatments (104). Because B2C10 was unable to detach galectin-1 while boosting TIL function, we concluded that detaching galectin-3 from TIL is sufficient to restore function, while not excluding a contribution of other galectins. We have so far failed to identify an anti-galectin-1 antibody able to detach galectin-1 from cells and are therefore unable to examine if galectin-1 also plays a role in TIL dysfunction.

How do galectins influence the distribution of T cell surface molecules?

Galectin-3 is an abundant lectin in many solid tumors and carcinomatous ascites. It can thus bind to surface glycoproteins of TIL. Glycoproteins often bear multiple copies of the sugar moieties that are recognized by galectins. The multivalent nature of galectin-glycan interactions results in high avidity in the range of 106 M−1, and allows the formation of galectin-glycoprotein lattices (reviewed elsewhere (105)). Similarly, lattices on TIL, formed by glycosylated surface receptors and extracellular galectin-3, would reduce the mobility of the former molecules, a fact that could explain the impaired function of TIL. The release of galectin-3 by soluble galectin ligands would restore the mobility of glycosylated surface receptors and boost IFN-γ secretion by TIL. Anti-galectin-3 antibody B2C10 should have a similar effect: this antibody binds to the N-terminal region of the galectin-3 and its rigid structure could prevent association of galectin-3 monomers mediated by the N-terminal region, thereby affecting the oligomerization of the lectin. Antibody B2C10 was shown to inhibit erythrocyte agglutination mediated by galectin-3 oligomerization (104).

The presence of galectin-glycoprotein lattices is in agreement with our observations with CTL clones and TIL. TCR and CD8 molecules are not co-localized on dysfunctional T cells and treating dysfunctional T cells with either an anti-galectin-3 antibody or galectin ligands detached galectin-3 from the T cell surface and restored the TCR-CD8 co-localization estimated by FRET (91, 99). Considering that HLA-peptide tetramer binding requires TCR and CD8 cooperation, the disorganization of galectin-glycoproteins lattices in the presence of galectin ligands could explain the recovery of HLA-peptide tetramer binding on dysfunctional CTL clones that were treated with LacNAc (91).

A number of publications suggest that several human T cell surface glycoproteins can be linked together by galectins and form lattices. Human TCR α-chain, in contrast to the β-chain, has been shown to harbor complex N-glycans, the major natural ligands for galectin-3 (106, 107). The removal of an N-glycosylation site from a human TCR α-chain was reported to result in increased avidity of T cells grafted with the gene encoding the modified TCR (108). Galectin-3 was reported to bind to CD45, CD29, CD43, and CD71 (109), and galectin-1 to CD45, CD7 and CD43 (110). Galectin-1/CD7 ligation was shown to induce apoptosis of CD4 T lymphocytes (111). It has also been shown by immunoprecipitation that galectin-3 binds to CD45 and that galectin-3 influences the CD45 partition to microdomains containing the TCR (112). Interestingly, CD45-TCR proximity is known to negatively regulate the TCR signaling cascade (113).

Glycosylation changes at the T cell surface

To explain that galectin-3, alone or together with galectin-1, inhibits functions of recently activated T cells, we surmised that the recently activated T cells, compared to resting T cells, harbor a set of glycans that are either more numerous or better ligands for galectin-3. We stimulated resting CTL in the presence of swainsonine that inhibits α-mannosidase II involved in the N-glycosylation pathway. Compared to untreated cells, cells stimulated in the presence of swainsonine showed on day 4 a better TCR-CD8 co-localization and a higher ability to release IFN-γ upon antigenic stimulation (91).

We also characterized global changes in surface N- and O-glycans on two human CTL clones that were collected either in a resting state, 14 days after antigenic stimulation, or in a recently activated state, four days after antigenic stimulation. Applying ultra-sensitive MALDI-TOF-MS, combined with various glycosidase digestions and GC-MS linkage analyses, we made two novel observations.

Firstly, the N-glycome of recently activated cells versus resting cells consists of longer LacNAc chains, of which a portion contains more than four LacNAc moieties (poly-LacNAc). Secondly, it contains more multi-antennary N-glycans (114). Interestingly, our results showed that the above poly-LacNAc chains appeared to be equally distributed on all available N-glycan branches and not selectively enriched on a specific branch. In contrast, murine T cells are poor in tri- and tetra-antennary poly-LacNAc glycans (115). This difference could potentially explain the crucial role in mice of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V (Mgat5), an enzyme essential for the generation of complex tetra-antennary N-glycan, as T cells from mice lacking Mgat5, compared to their wildtype counterparts, are more sensitive to activation and have reduced poly-LacNAc motives (92). The glycome modifications observed on human CTL clones upon activation are expected to increase the number of galectin-3 natural ligands, but also the number of galectin-1 ligands, and favor lattices that could reduce the mobility of surface glycoproteins, as the affinity of both galectins was reported to be much higher when repeated LacNAc units are present (116).

We also observed that recently activated CTL clones exhibited a lower abundance of terminal a2,6-linked NeuAc residues than resting CTL (114). Galectin-1 binds to terminal LacNAc units, even if they are decorated with a2,3-linked NeuAc. On the contrary, galectin-1 binding is blocked by the presence of terminal a2,6-linked NeuAc (88, 110, 111, 117, 118). Our glycome analyses suggest therefore that more galectin-1 natural ligands are presented on recently activated CTL versus resting CTL.

All together, the results of our glycome analyses of CTL clones combined with the fact that functions of both CTL clones and TIL can be boosted by galectin ligands, support our working hypothesis: TIL are in permanent contact with tumor cells and have been stimulated by antigen recently. The resulting activation of T cells modifies the expression profiles of enzymes of the N-glycosylation pathway, increasing the expression of N-glycans at the T cell surface. Considering the high abundance of extracellular galectins in tumors, secreted by tumor cells and macrophages, this could favor the formation of galectin-glycoprotein lattices and therefore the dysfunction of some TIL.

Towards a clinical trial combining vaccination and galectin-binding polysaccharides

As described above, treating TIL with modified citrus pectin GCS-100 improved their ability to secrete IFN-γ upon stimulation. We decided therefore to test the therapeutic effect of GCS-100 in tumor-bearing mice. We injected 40 mice subcutaneously in the flank with 2x106 P815 mastocytoma cells. On day 4, half of the animals were vaccinated with an adenovirus encoding P815 tumor antigen P1A (5). Therapeutic vaccination has thus far proven ineffective at inducing tumor rejection in tumor-bearing mice (Catherine Uyttenhove & Guy Warnier, personal communication). On day 10, treatments with either PBS or GCS-100 were initiated three times a week. Three weeks later, the tumor had become undetectable in six out of the ten vaccinated mice treated with GCS-100, of which five were still alive after another three months. Control mice that received only the vaccine died. In non-vaccinated mice, the polysaccharide had no visible effect by itself. These results suggest that a combination of galectin-3 ligands and therapeutic vaccination may induce more effective tumor regression in cancer patients than vaccination alone. Setting up a clinical trial combining anti-tumoral vaccination and GCS-100 was impossible because the pharmaceutical company that produced the GCS-100 declared bankruptcy.

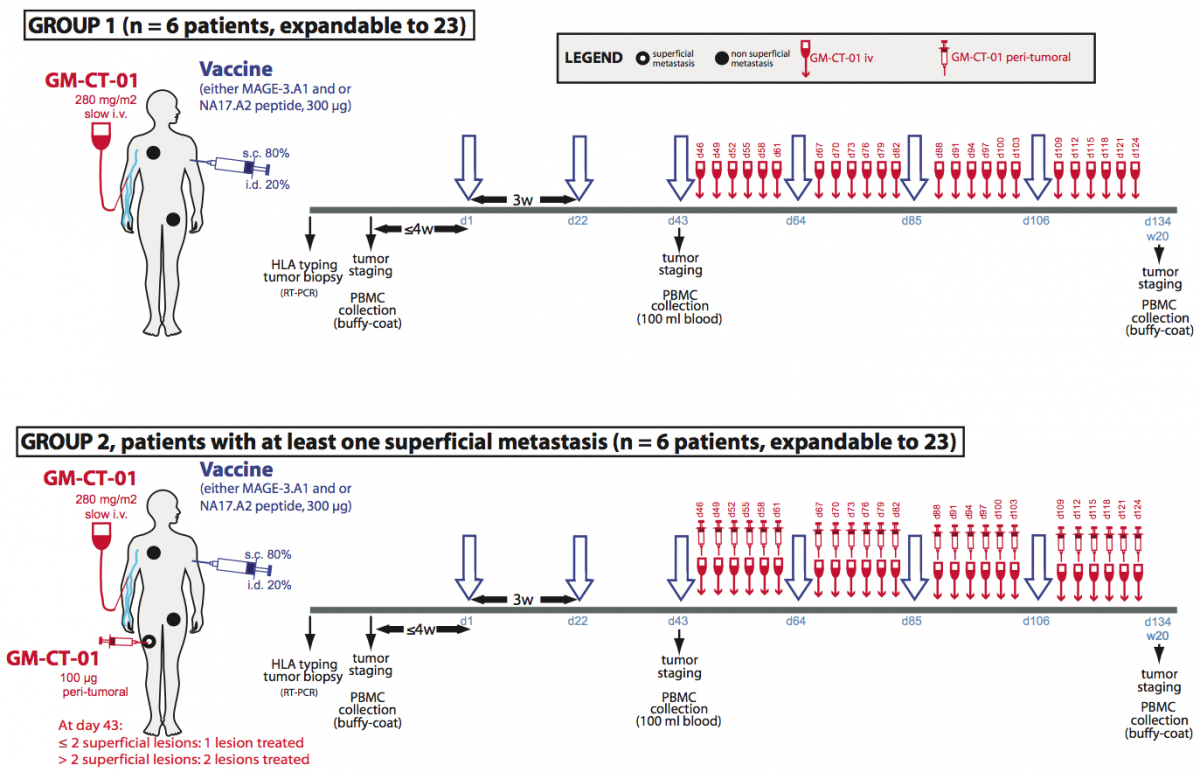

GM-CT-01, a galactomannan derived from guar gum, has been shown to bind to galectin-1 (119), and to increase the anti-tumor activity of chemotherapy drug 5-fluorouracil. It was previously injected in patients with solid tumors without major side effects (120). We have treated TIL samples with GM-CT-01 and the first results are encouraging. We therefore will launch a Phase I/II clinical trial combining peptide vaccination associated with intravenous injections of GM-CT-01 in patients with advanced melanoma (Fig.1). Patients will receive sequential vaccinations with one or two peptides, MAGE-3.A1 and NA17.A2, matching the tumor antigens expressed by their tumor. Their formulation and schedule of vaccination (timing, dose, route of administration) will be similar to previous trials with these peptides (15, 20, 21). GM-CT-01 will be administered systemically by repeated intravenous infusions, in order to ensure a prolonged effect on tumor-associated lymphocytes. The treatment dose matches the total cumulative dose in previous GM-CT-01 treatment schedules (120). For selected patients with cutaneous or subcutaneous metastases, in addition to systemic GM-CT-01, small amounts of this drug will be injected close to metastases, to increase local concentration of the drug.

Figure 1. Treatment plan of the clinical trial involving GM-CT-01.

Treatment allocation: Patients will be divided in two treatment arms. Both will run in parallel. Patients with at least one measurable lesion will be assigned to group 1 and will receive the following treatment: peptide vaccinations and systemic GM-CT-01 injections. Patients with at least one measurable and at least one superficial metastasis will be assigned in priority to group 2 and will receive the following treatment: peptide vaccinations, systemic GM-CT-01 administrations and peri-tumoral administration of GM-CT-01 in one or two superficial metastases.

Human tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes show impaired IFN-γ secretion

Both human CD8 and CD4 tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes (TIL) were isolated from tumor ascites or solid tumors and compared with T lymphocytes from blood donors. TIL secrete low levels of INF-γ and other cytokines upon non-specific stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. TCR were observed to be distant from the co-receptors on the cell surface of TIL, either CD8 or CD4, whereas TCR and the co-receptors co-localized on blood T lymphocytes.

TCR and CD8 do not co-localize on CD8 T cells with impaired functions (in collaboration with P. Vandersmissen and P. Courtoy, PICT/SSS)

Reversing the anergy of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes with galectin antagonists

We have attributed the decreased IFN-γ secretion to a reduced mobility of T cell receptors upon trapping in a lattice of glycoproteins clustered by extracellular galectin-3. Indeed, we have shown that treatment of TIL with N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc), a galectin antagonist, restored this secretion.

Treatment of tumor-infitrating lymphocytes with a galectin antagonist reverses

Our working hypothesis is that TIL have been stimulated by antigen chronically, and that the resulting activation of T cells could modify the expression of enzymes of the N-glycosylation pathway, as shown for murine T cells. The chronically activated TIL, compared to resting T cells, could thus express surface glycoproteins decorated with a set of glycans that are either more numerous or better antagonists for galectin-3. Galectin-3 is an abundant lectin in many solid tumors and carcinomatous ascites, and can thus bind to surface glycoproteins of TIL and form lattices that would thereby reduce TCR mobility. This could explain the impaired function of TIL. The release of galectin-3 by soluble competitor antagonists would restore TCR mobility and boost IFN-γ secretion by TIL. We recently strengthened this hypothesis by showing that both CD4 and CD8 TIL that were treated with an anti-galectin-3 antibody, which could disorganize lattice formation, had an increased IFN-γ secretion compared to untreated cells.

Towards a clinical trial combining vaccination and galectin-binding polysaccharides

Galectin competitor antagonists, e.g. disaccharides LacNAc, are rapidly eliminated in urine, preventing their use in vivo. We recently found that a plant-derived polysaccharide, currently in clinical development, detached galectin-3 from TIL and boosted their IFN-γ secretion. Importantly, we observed that not only CD8+ TIL but also CD4+ TIL that were treated with this polysaccharide secreted more IFN-γ upon ex vivo re-stimulation. In tumor-bearing mice vaccinated with a tumor antigen, injections of this polysaccharide led to tumor rejection in half of the mice, whereas all control mice died. In non-vaccinated mice, the polysaccharide had no effect by itself. These results suggest that a combination of galectin-3 antagonists and therapeutic vaccination may induce more tumor regressions in cancer patients than vaccination alone. Translation of these results to the clinic was unfortunately impossible because the company producing this polysaccharide got bankrupted. We recently identified another plant-derived polysaccharide that binds to galectins and was already used in combination with chemotherapy in phase II clinical trials in colorectal cancer patients. This compound was as effective as LacNAc in boosting the secretion of IFN-γ by treated TIL. A clinical trial with this new compound, in combination with anti-tumoral vaccination was launched in 2013 in clinical centers close to the de Duve Institute. We are currently trying to understand the very early activation events that are defective in TIL.

Further reading

Antonopoulos A, Demotte N, Stroobant V, Haslam SM, van der Bruggen P, Dell A. 2012. Loss of effector function of human cytolytic T lymphocytes is accompanied by major alterations in N- and O-glycosylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287: 11240-11251

Demotte N, Wieërs G, Van Der Smissen P, Moser M, Schmidt CW, Thielemans K, Squifflet J-L, Weynand B, Carrasco J, Lurquin C, Courtoy PJ, van der Bruggen P. 2010. A galectin-3 ligand corrects the impaired function of human CD4 and CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and favors tumor rejection in mice. Cancer Research, 70: 7476-7488

Demotte N, Stroobant V, Courtoy PJ, Van der Smissen P, Colau D, Luescher IF, Hivroz C, Nicaise J, Squifflet J-L, Mourad M, Godelaine D, Boon T, van der Bruggen P. 2008. Restoring the association of the T cell receptor with CD8 reverses anergy in human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Immunity, 28: 414-424

Demotte N, Colau D, Ottaviani S, Godelaine D, Van Pel A, Boon T, van der Bruggen P. 2002. A reversible functional defect of CD8+ T lymphocytes involving loss of tetramer labeling. European Journal of Immunology, 32: 1688-1697

Petit AE, Demotte N, Scheid B, Wildmann C, Bigirimana R, Gordon-Alonso M, Carrasco J, Valitutti S, Godelaine D, van der Bruggen P.

Nat Commun. 2016; 7:12242.

Demotte N, Bigirimana R, Wieërs G, Stroobant V, Squifflet JL, Carrasco J, Thielemans K, Baurain JF, Van Der Smissen P, Courtoy PJ, van der Bruggen P.

Clin Cancer Res. 2014; 20(7):1823-33.

Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P, Boon T.

Nat Rev Cancer. 2014; 14(2):135-46.

Demotte N, Wieërs G, Van Der Smissen P, Moser M, Schmidt C, Thielemans K, Squifflet JL, Weynand B, Carrasco J, Lurquin C, Courtoy PJ, van der Bruggen P.

Cancer Res. 2010; 70(19):7476-88.

François V, Ottaviani S, Renkvist N, Stockis J, Schuler G, Thielemans K, Colau D, Marchand M, Boon T, Lucas S, van der Bruggen P.

Cancer Res. 2009; 69(10):4335-45.

Demotte N, Stroobant V, Courtoy PJ, Van Der Smissen P, Colau D, Luescher IF, Hivroz C, Nicaise J, Squifflet JL, Mourad M, Godelaine D, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

Immunity. 2008; 28(3):414-24.

Annu Rev Immunol. 2006; 24:175-208. Review.

Zhang Y, Sun Z, Nicolay H, Meyer RG, Renkvist N, Stroobant V, Corthals J, Carrasco J, Eggermont AM, Marchand M, Thielemans K, Wölfel T, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

J Immunol. 2005; 174(4):2404-11.

Demotte N, Colau D, Ottaviani S, Godelaine D, Van Pel A, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

Eur J Immunol. 2002; 32(6):1688-97.

Schultz ES, Chapiro J, Lurquin C, Claverol S, Burlet-Schiltz O, Warnier G, Russo V, Morel S, Lévy F, Boon T, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P.

J Exp Med. 2002; 195(4):391-9.

Schultz ES, Lethé B, Cambiaso CL, Van Snick J, Chaux P, Corthals J, Heirman C, Thielemans K, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

Cancer Res. 2000; 60(22):6272-5.

Chaux P, Luiten R, Demotte N, Vantomme V, Stroobant V, Traversari C, Russo V, Schultz E, Cornelis GR, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

J Immunol. 1999; 163(5):2928-36.

Chaux P, Vantomme V, Stroobant V, Thielemans K, Corthals J, Luiten R, Eggermont AM, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

J Exp Med. 1999; 189(5):767-78.

Mandruzzato S, Brasseur F, Andry G, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

J Exp Med. 1997; 186(5):785-93.

Boël P, Wildmann C, Sensi ML, Brasseur R, Renauld JC, Coulie P, Boon T, van der Bruggen P.

Immunity. 1995; 2(2):167-75.

van der Bruggen P, Bastin J, Gajewski T, Coulie PG, Boël P, De Smet C, Traversari C, Townsend A, Boon T.

Eur J Immunol. 1994; 24(12):3038-43.

van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, Boon T.

Science. 1991; 254(5038):1643-7.

DISFUNCTIE VAN T-LYMFOCYTEN IN TUMOREN